Story:

Abram Goldberg: political protege

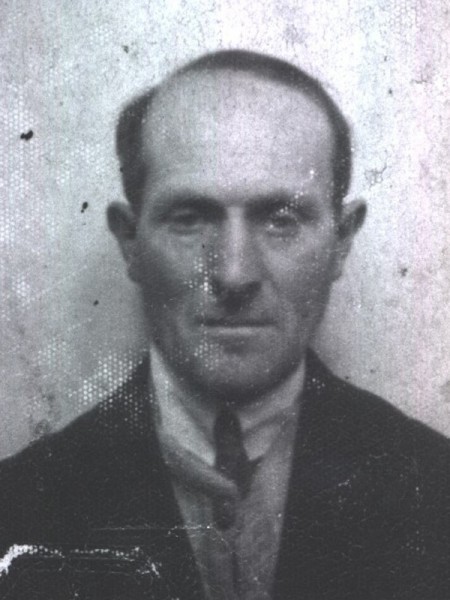

Abram (Abe) Goldberg was only fourteen years old when war began. He had already been active in the Bund (Jewish socialist) youth organisation since he was ten years old. In the ghetto he befriended Bono Wiener. Bono looked after the younger Abe, and got him involved in the political underground. Before the ghetto was liquidated they collected and buried two boxes of documents and photos, one of which was retrieved by Abe after the war.

Abram was born 5 October 1924 in Lodz. His father, Hersch was a textile worker, and his mother, Chaja, a homemaker. He also had three sisters. After Germany’s invasion of Poland, the Goldberg family were deported from Lodz to Radogoscz concentration camp, before being sent to a makeshift camp near Krakow. Abe and his parents travelled illegally back to Lodz, leaving Abe’s two sisters, Estera and Frania, behind. They intended to return to collect the girls, but after the closing of the Lodz ghetto in May 1940, Abe’s father was unable to reach them. They did not see them again. When the Goldbergs returned to Lodz, they found a room in the same apartment as the Wiener family, and Abe and Bono became good friends. Bono was a supervisor at a metal factory and despite Abe’s lack of experience, gave him a position as deputy foreman.

During September 1942, a mass deportation occurred in the Lodz ghetto in which 15,859 children, elderly and ill inhabitants were transported to Chelmno extermination centre. Abe’s father, aunts and six cousins were caught hiding during selections and included on the transports. Abe and his mother somehow carried on, working and starving in the ghetto. At the beginning of August 1944 the Germans commenced the liquidation of the ghetto and deportation to Auschwitz. Abe and his mother decided to go into hiding in the ceiling of their apartment. During the night, they could leave their hiding place to find food and water. After four weeks Chaja decided to present herself for deportation, so Abe accompanied her. When they arrived in Auschwitz, they were separated immediately, and Chaja was sent directly to the gas chambers.

Abe worked as a metal worker in Auschwitz, then was transferred to Braunschwieg camp in Germany where he cleaned engine parts in a truck construction factory. During March 1945, inmates from Braunschweig were forced on a death march to Watenstadt, then sent to Ravensbruck camp and later transferred to Wobbelin, where he was liberated on 2 May 1945.

After the war, Abe returned to Poland to collect the buried boxes of artefacts. He worked for the Bund organisation, assisting Jews to escape Poland and find new homes. He met and married survivor Cesia Amatensztein in Belgium. They decided to leave Poland, where the majority of their families were murdered, apart from Abe’s sister Maryla, who had moved to the Soviet Union with her husband before the war. Abe and Cesia immigrated to Melbourne. He became involved with the Melbourne Holocaust Museum in 1984 where he served as treasurer and is still active as a museum guide and member of the Board.

Back to top

Story:

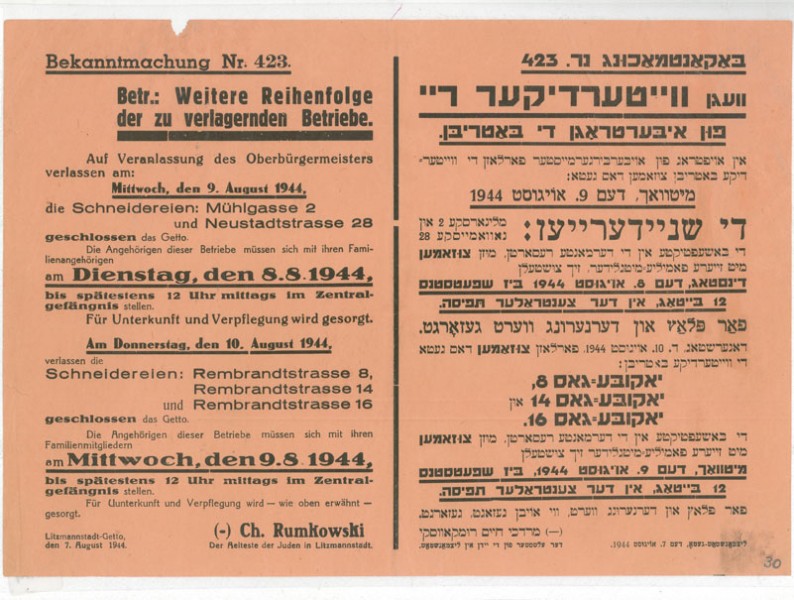

Burying the boxes

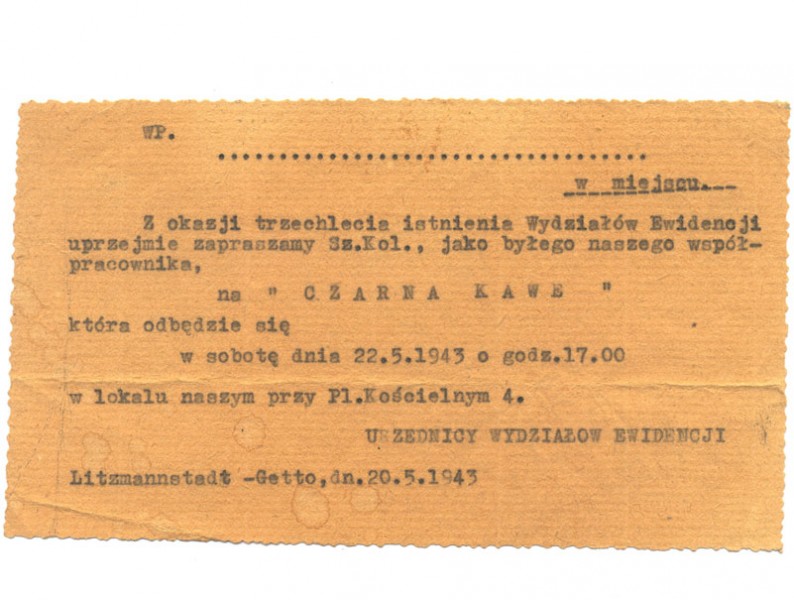

Secretly, in 1942, Bono Wiener and Abram Goldberg began collecting artefacts in the Lodz ghetto. They hid the material in their apartment attic. The items included official ghetto notices and orders, ration cards, work cards, an illegally-constructed radio, as well as a variety of other invaluable documents. Both Abram and Bono were politically active in the Bund (a Jewish socialist organisation) and collected the material as evidence of the conditions in the ghetto. The items testify to Rumkowski’s authoritarian rule of the ghetto, and give an insight into the hardships faced by ghetto inhabitants.

During the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto, between July and August 1944, Abram and Bono hid two metal boxes containing the artefacts. One was buried under a toilet, which they hoped would deter thieves, owing to the stench. The second box was buried in a garden under trees. After liberation, Abram, who heard that Bono had died in Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, returned to Lodz in May 1945. Although he retrieved the box hidden in the toilet, he failed to find the second box containing the radio and some of his diaries.

Back to top

Story:

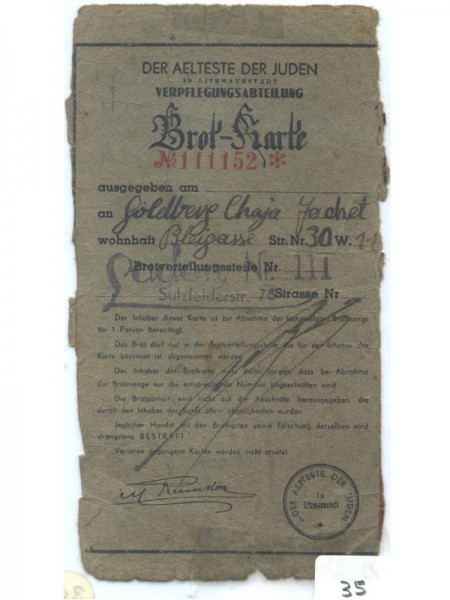

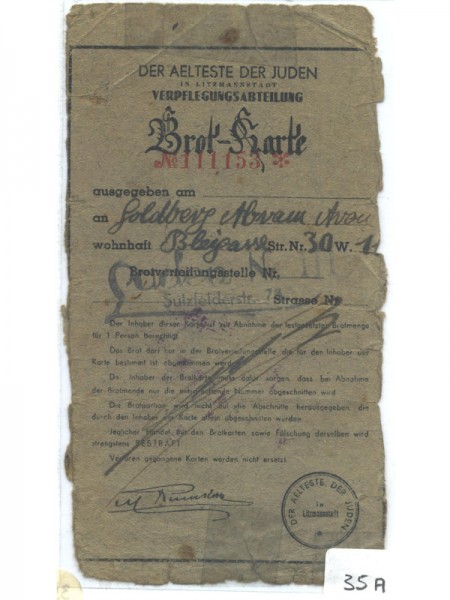

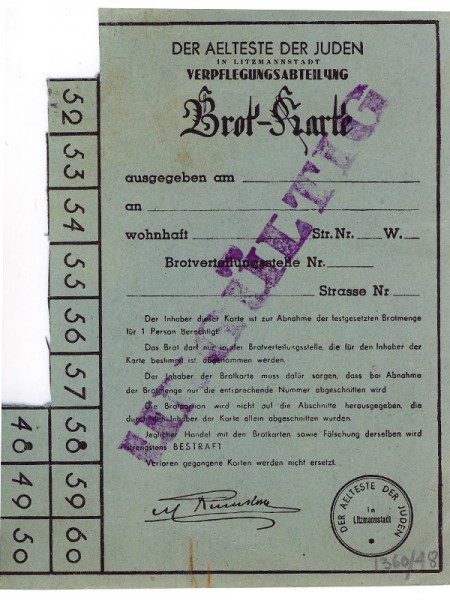

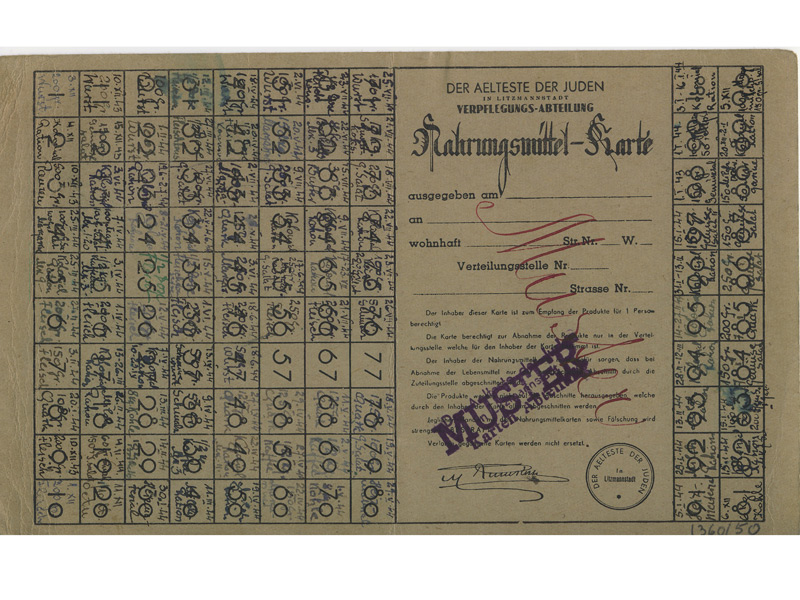

Food ration cards

Food was in short supply in the ghetto, so in order to receive it, you needed ration cards, and in order to obtain this card you needed to be registered to work. Upon receiving the ration, a section of the card would be torn off. Complaints of insufficient food were rife amongst inhabitants and starvation was one of the major contributors to death in the ghetto.

According to Bono Wiener: “Hunger in the ghetto was a permanent part of our lives… When you don’t have enough food for weeks or for months it becomes a part of your life. You live with it, you sleep with it, you dream of it, you talk about it. So hunger was a part of the life in the ghetto even for the person who ate their (allotted loaf of) bread in one go, or the person who divided it and had a little bit (each day). We didn’t think about anything else because there was never enough… we had four years of permanent starvation. Four years – day and night – we didn’t have enough food”.

Back to top

Story:

Last letter from Estera

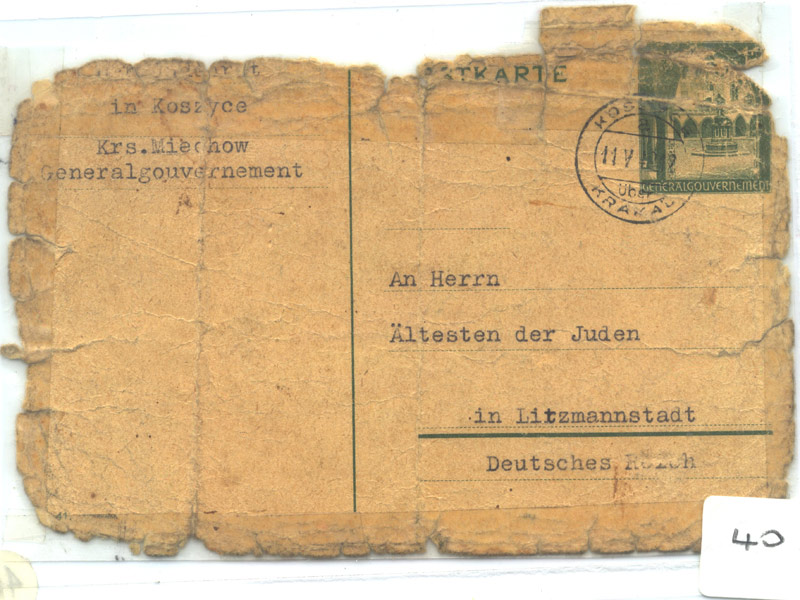

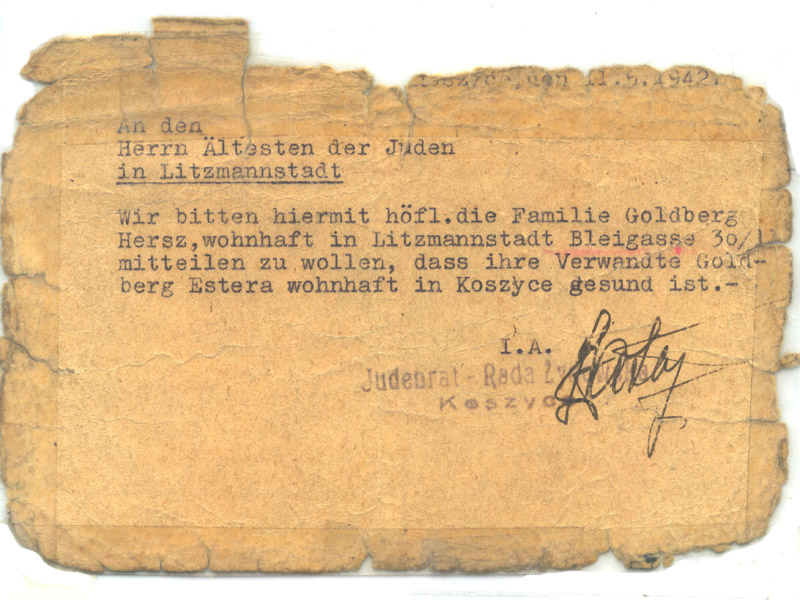

After Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Goldberg family were deported from their hometown of Lodz to Radogoscz concentration camp, before being sent to a makeshift camp near Krakow. Abram’s parents, Hersch and Chaja, had Bund connections in Krakow, which enabled them to travel illegally back to Lodz. Abram went with them but they left his two unmarried sisters, Estera and Frania, behind. The Goldbergs intended to return to collect the girls, but after the closing of the Lodz ghetto on 1 May 1940, they were unable to reach them. The family received irregular letters from Estera, including this postcard on 11 May 1942, informing them that Estera was now residing in Koszyce.

Abram recalls: “In 1942 this came in the ghetto, addressed, not to us personally, but to the Elders of the Jews in Litzmannstadt (Lodz). On the other side, was printed that my sister, Estera Goldberg, was living in Germany. To let us know that she was alive and well? Was she still alive at this time? I don’t know. It is her name. The signature was supposed to be from the Judenrat (Jewish Council) in Koszyce.”

It is difficult to ascertain whether this document was written by Estera herself, and whether she was even alive by 1942 because the Nazis often forced camp inmates to write to their loved ones, allaying their fears about deportation in an attempt to convince others to join them. Sometimes inmates were forced to write multiple letters, which would be posted after the author’s death. Abram never found out the fate of either of his sisters. His third sister, Maryla, survived because she had moved to the Soviet Union with her husband.