Story:

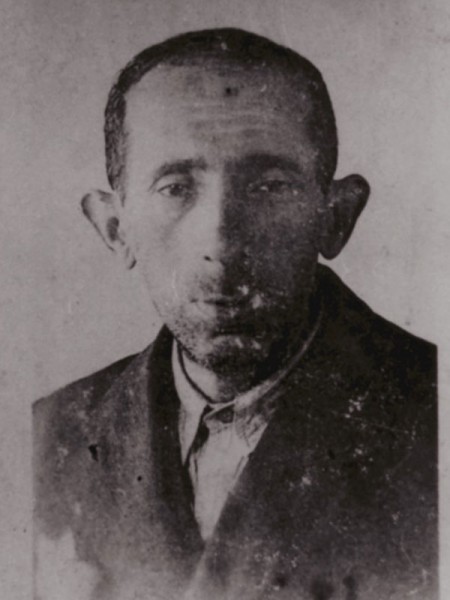

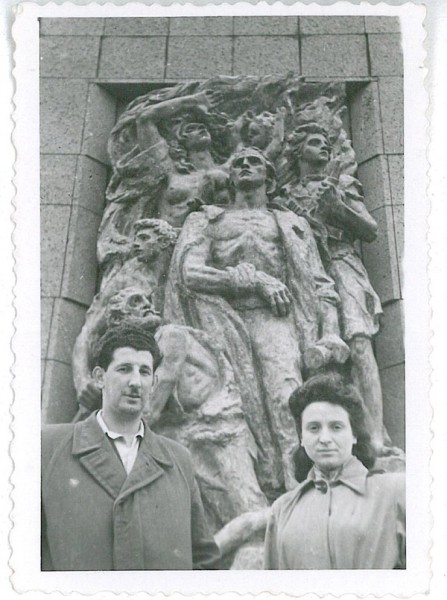

Bono Wiener: political activist

Bono Wiener was 19 years old when war broke out. He was already politically astute, having been brought up with parents active in the Bund movement, a Jewish socialist organisation. In the ghetto he was involved in the resistance movement, and finally, when the ghetto was being liquidated, he was prescient enough to understand the importance of burying documents from the ghetto for the future. While others were thinking about their own survival, Bono had the foresight to see the value in preserving documentary evidence of the Nazi crimes.

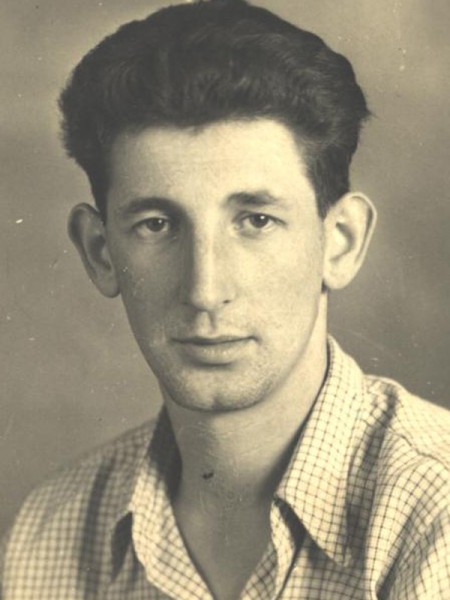

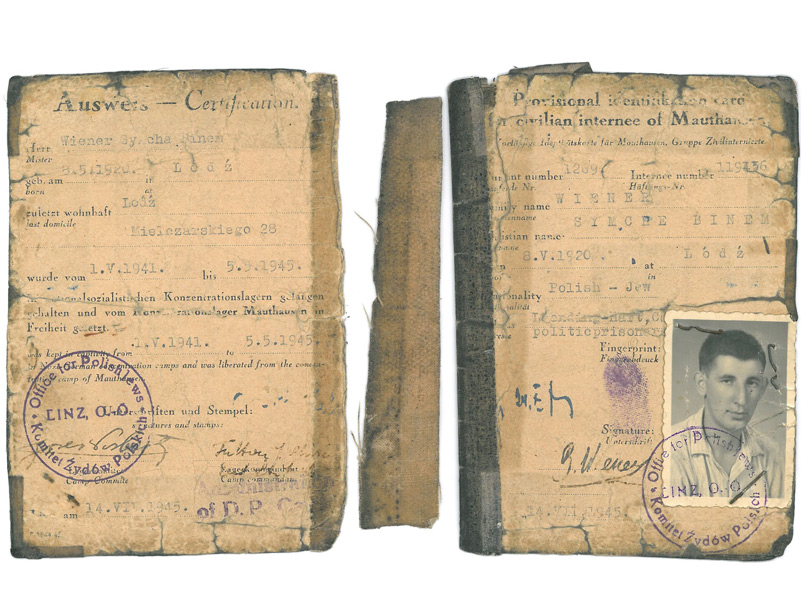

Symcha-Binem (Bono) Wiener was born in Lodz in 1920. His father, Mosche, ran a transportation business. His mother, Royze, was involved in the Bund’s women’s organisation. His brother, Pinchas, was a conscript of the Polish Army and spent most of the war in Russia. Bono was a member of the Bund Youth Organisation, the Socialister Kinder Yiddish Farband (SKIF) and was employed as a mechanic in a textile factory when he finished school.

In May 1940, the Wiener family moved in to the ghetto where Bono was employed in a metal factory. He joined the Bund leadership in the ghetto, a group banned by the Nazis. The organisation met in cells to avoid detection and was instrumental in improving the lives of inhabitants in the ghetto. They established a soup kitchen, organised cultural activities, and with the help of Bono, constructed a radio, which gave them access to information about both Nazi and Allied activities. Bono’s father died of starvation on 16 May 1942, while his mother passed away on 30 June 1944, due to complications from kidney surgery. After his mother’s death, Bono’s Aunt Clara was chosen for deportation from the ghetto, so Bono volunteered to accompany her. The couple arrived in Auschwitz on 25 August 1944 and were immediately separated. Bono never saw his aunt again. Bono obtained a position as a toolmaker in Auschwitz and was once again involved in the underground movement.

In mid-January 1945 Bono, aged 24, was sent on a death march to Mauthausen concentration camp. Many prisoners froze to death along the way, due to the harsh Polish winter or were shot by the German guards. Bono survived and was soon employed in a factory in Mauthausen, building planes for the German administration. The United States Army liberated the camp on 5 May 1945.

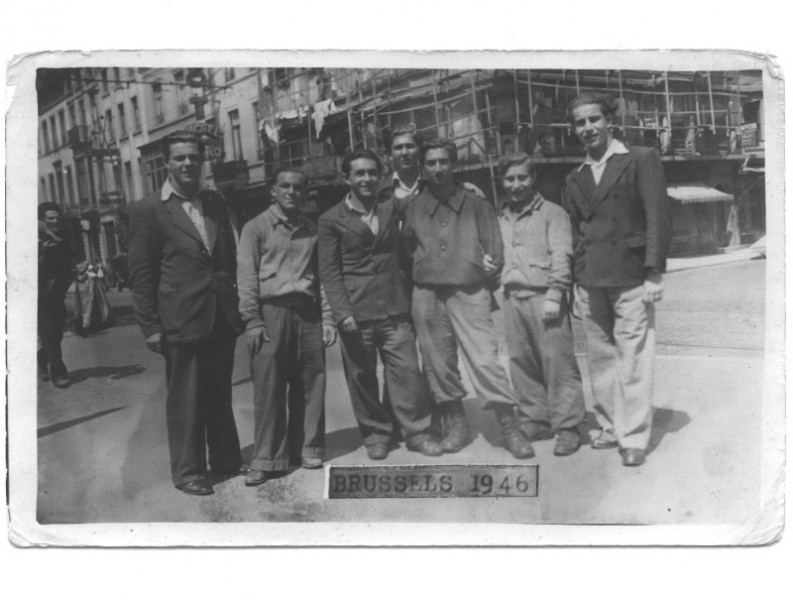

Bono did not believe it was possible to rebuild a Jewish life in Poland, and immigrated to Australia with his brother in 1950. Bono became active in the Australian Labor Party, was a secretary and president of the Bund, and was one of the Founders of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum in Elsternwick, where he worked as co-president. He died on 9 July 1995.

Back to top

Story:

The Bund

The Bund was a Jewish community organisation that strove to improve life in the ghetto, by establishing a soup kitchen, and sporting and cultural activities. The Nazis banned the group, so members met in small groups to avoid detection. Although wide scale armed resistance was impossible in Lodz, due to Rumkowski’s authoritarian rule and the ghetto’s isolation from the outside world, the Bund contributed in other ways. They organised resistance activities such as removing parts from products which were being manufactured for the Germans, and attempting to procure and construct weapons.

Bund, an abbreviation for ‘the General Jewish Labour Bund of Lithuania, Poland and Russia’, was a secular Jewish socialist party founded in Vilnius, Russia in 1897. They sought to unite all Jewish workers in the Russian Empire into a united socialist party. The Russian Empire then included Lithuania, Latvia, Belorus, Ukraine and most of present-day Poland. The Bund came to oppose Zionism, arguing that emigrating to Palestine was a form of escapism. They promoted the use of Yiddish as a national Jewish language, rather than reviving Hebrew, as Zionists preferred. They had a youth group called ‘Tsukunft’ (Yiddish for future).

During the liquidation of the ghetto between July and August 1944, the Bund were instrumental in warning inhabitants to avoid joining transports to Auschwitz, and to help them hide in the ghetto for as long as possible.

Back to top

Story:

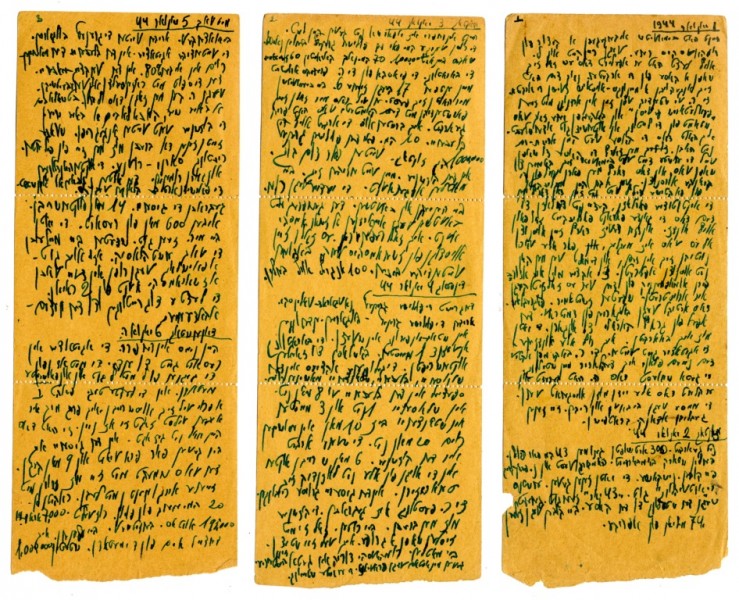

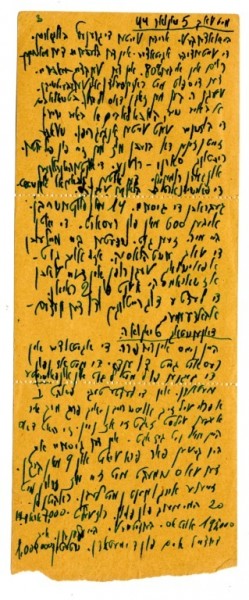

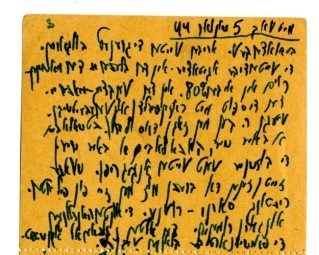

Bono’s Ghetto Notes

Bono Wiener took many notes as part of his resistance activities in the ghetto. The hand-writing is difficult to read and the notes are coded. He donated these notes among the items he donated after the war to YIVO, the Jewish Archive in New York.

Back to top

Story:

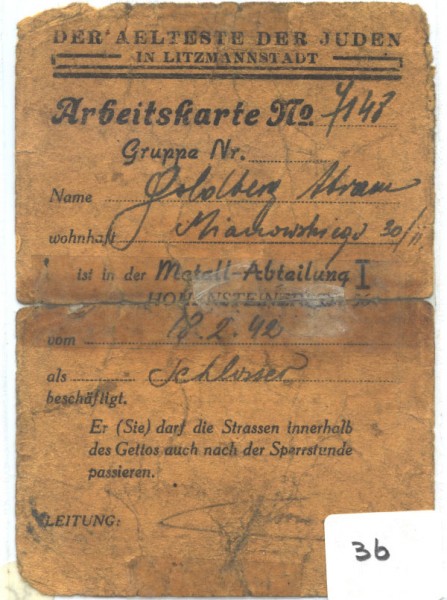

Burying the boxes

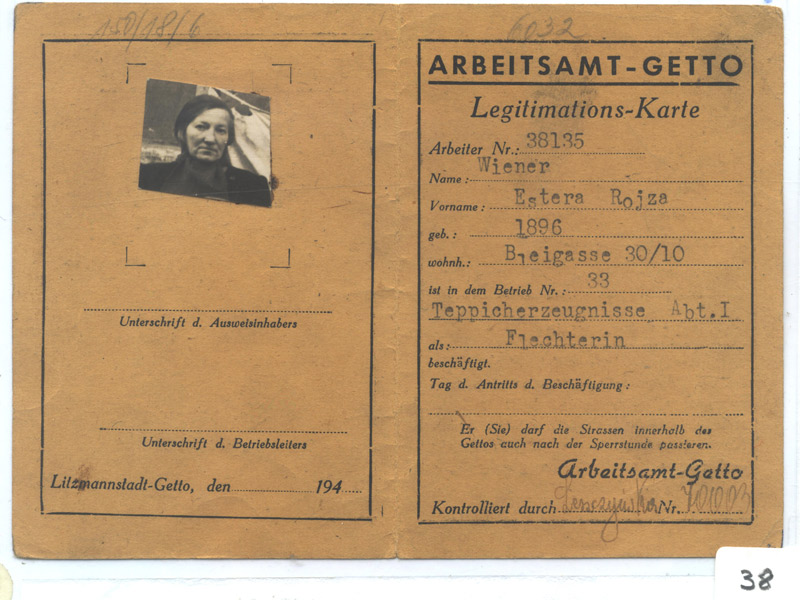

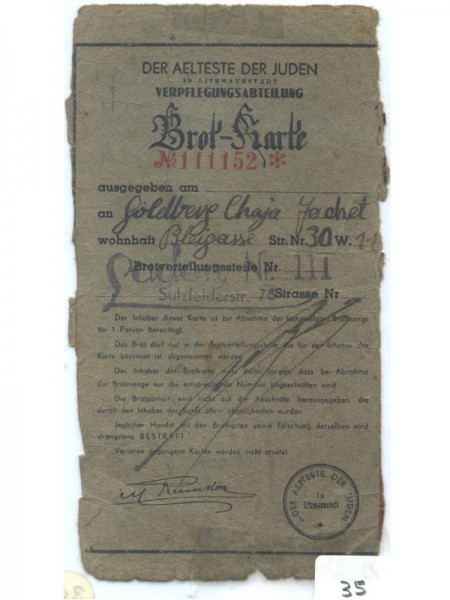

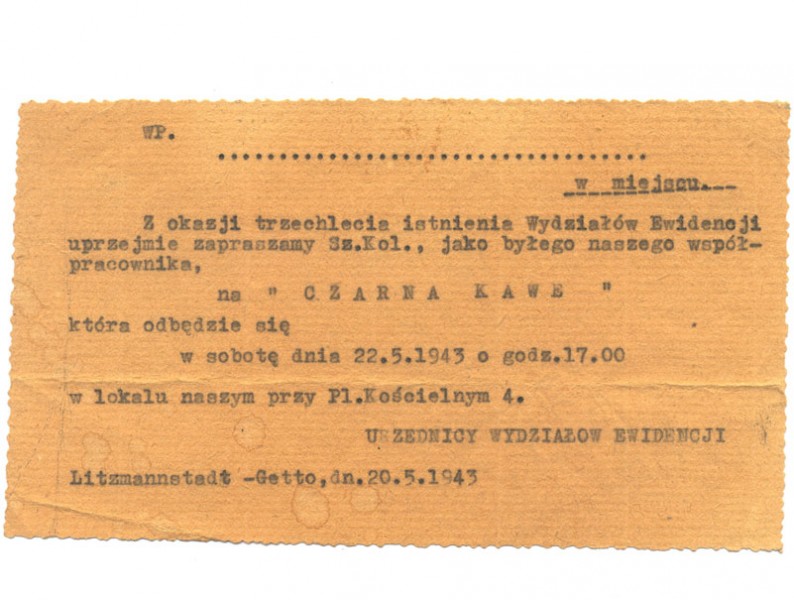

Secretly, in 1942, Bono Wiener and Abram Goldberg began collecting artefacts in the Lodz ghetto. They hid the material in their apartment attic. The items included official ghetto notices and orders, ration cards, work cards, an illegally-constructed radio, as well as a variety of other invaluable documents. Both Abram and Bono were politically active in the Bund (a Jewish socialist organisation) and collected the material as evidence of the conditions in the ghetto. The items testify to Rumkowski’s authoritarian rule of the ghetto, and give an insight into the hardships faced by ghetto inhabitants.

During the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto, between July and August 1944, Abram and Bono hid two metal boxes containing the artefacts. One was buried under a toilet, which they hoped would deter thieves, owing to the stench. The second box was buried in a garden under trees. After liberation, Abram, who heard that Bono had died in Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, returned to Lodz in May 1945. Although he retrieved the box hidden in the toilet, he failed to find the second box containing the radio and some of his diaries.

Back to top

Story:

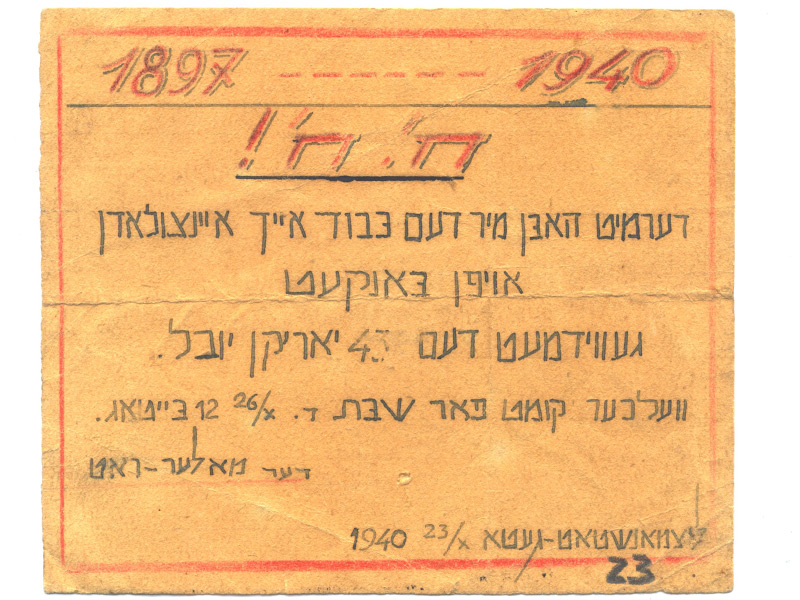

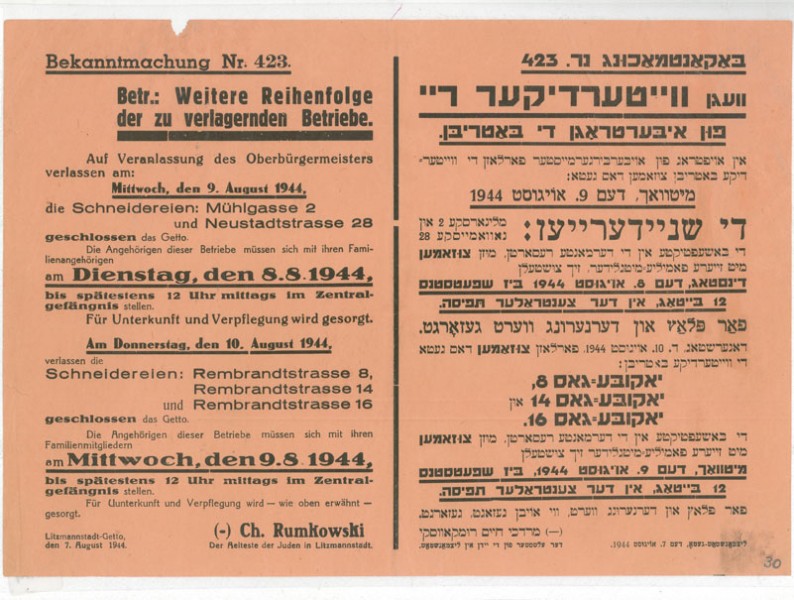

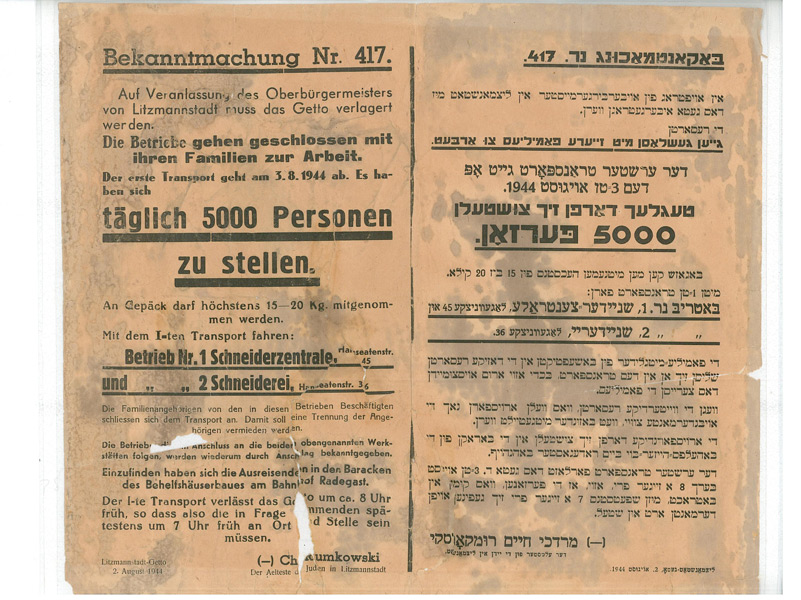

Deportation notice

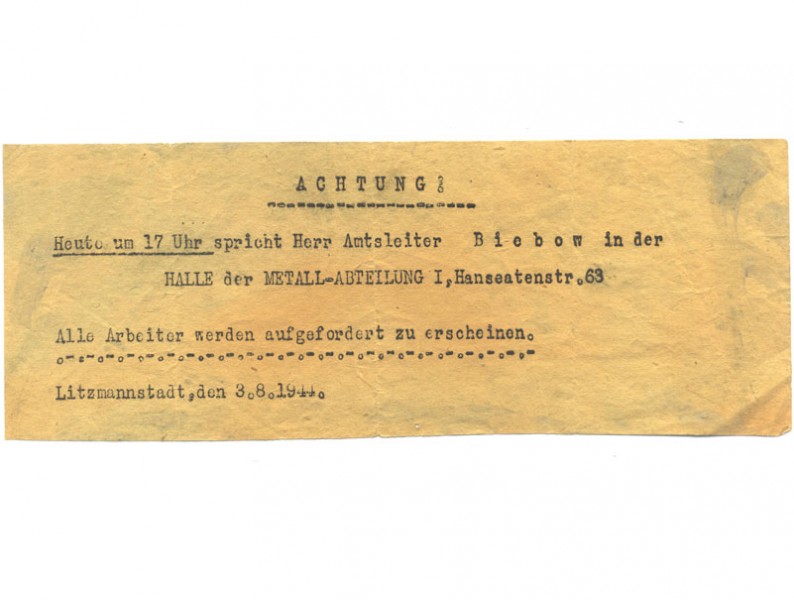

This notice, calling for the Jews to report for “relocation” to a new camp outside the ghetto, demonstrates the deceptive tactics used by the Nazis to give Jews false hope. By the time of this notice, August 1944, the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto was underway, having commenced in June, with regular deportations to Auschwitz. These deportations were disguised as “relocation” however the new location was never named. The Jews were also deceived into believing that by travelling with their families they would remain together. Yet the majority of family members were separated upon arrival at Auschwitz, and more than 80 per cent were murdered immediately in gas chambers. To add to the charade, this notice states that inhabitants can bring up to 20 kilograms of luggage with them, however they never saw this luggage again.

During August regular notices appeared in the ghetto, ordering 5,000 inhabitants per day, district-by-district, to present for “relocation”. However Jews were reluctant to report. The Bund (Jewish socialist organisation) warned Jews to hide in the ghetto for as long as possible. This particular notice orders workers and their families from two Tailoring Workshops in Hanseatenstreet to report at the Radegast station at 7 am on August 3, 1944.

Although Rumkowski signed this notice, his true authority became clear in the last few months of the ghetto’s existence. His attempts to prevent liquidation ultimately failed. The decision to liquidate the ghetto was made by the German administration, in an attempt to destroy the evidence. When the Soviet army arrived on 19 January 1945, they liberated 877 people. During June and August 1944, over 70,000 Lodz inhabitants were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, with the last transport departing on August 29, 1944 including Rumkowski and his family.

Back to top

Story:

Surviving Lodz

There were 223,000 Jews in Lodz at the start of war, but only around 10,000 of them survived. Starvation, disease and overwork killed many in the ghetto. Those that avoided this fate were sent to camps where they were either murdered upon arrival or died subsequently from overwork and malnutrition.

Only 500-600 Jews were left in the ghetto following the final liquidation in August 1944, to “clean up” the ghetto. Another 300 successfully hid from the deportations. On 19 January 1945, the Russian Army liberated 877 Jews from the ghetto. Slowly the surviving Lodz Jews returned and tried to find family, to see if any survived. Some tried to reclaim property and possessions, but this was extremely challenging. There was ongoing antisemitism in Poland, and many of the surviving Jews reported that they did not feel welcome. Many left, going to displaced persons camps to try to build new lives in new countries.

Back to top

Story:

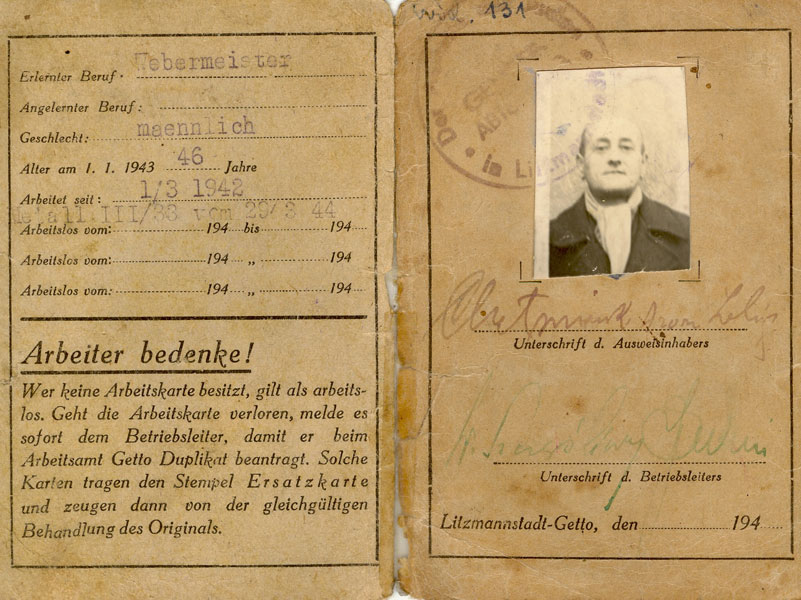

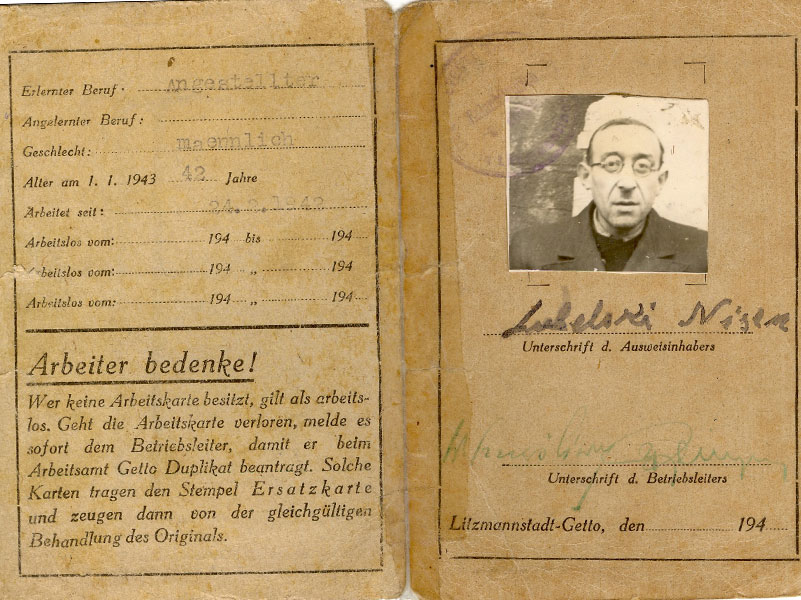

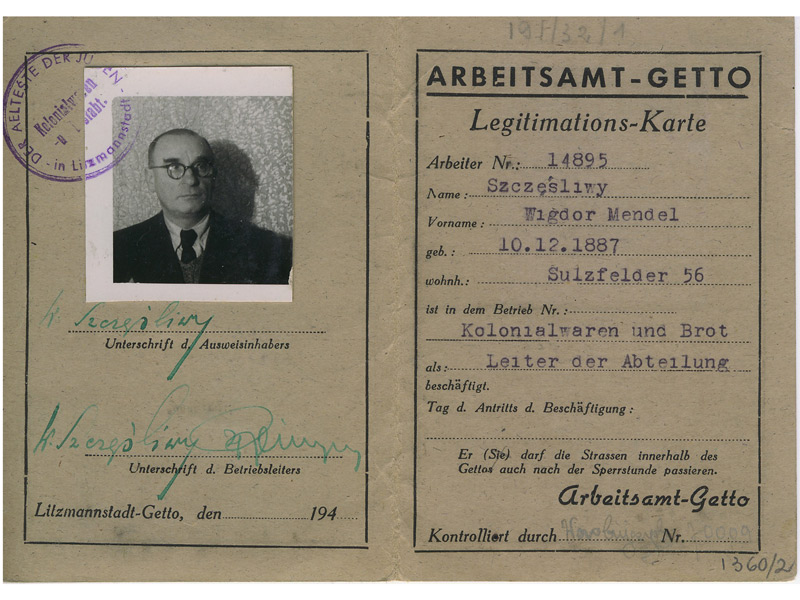

Work card

In order to survive in the ghetto, the Jews needed a work identity document, particularly as it ensured receipt of food rations. Work cards were a form of identification in the ghetto, which needed to be carried at all times.