Story:

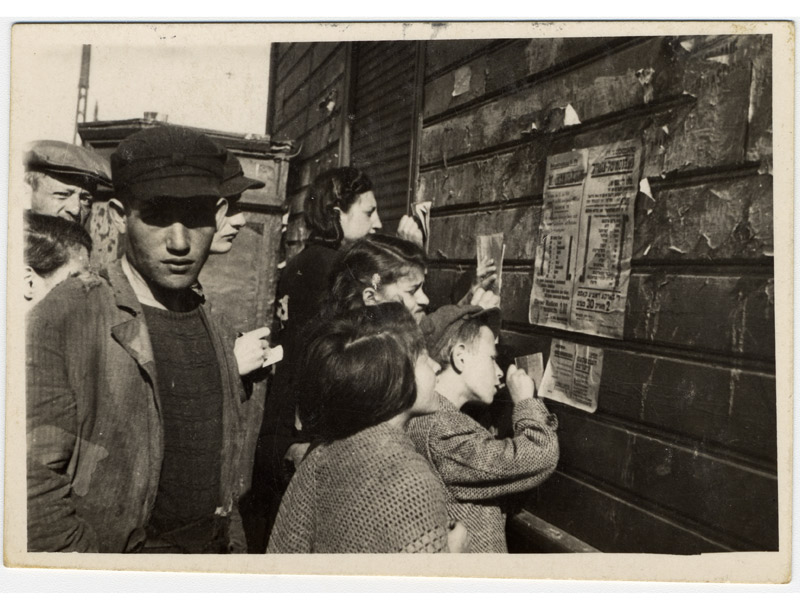

Control of information

As part of the strategy to control the Jews in the Ghetto, the Nazis completely sealed the ghetto area off and denied the populace access to information from the outside world. Phones, radios and newspapers were forbidden. Mail was strictly controlled and censored.

Back to top

Story:

Correspondence

Under Nazi rule, Jews were imprisoned in ghettos and camps and their access to information was tightly controlled. One way of doing this was through tight censorship of mail. Jews imprisoned in camps and ghettos could write to the outside world, but there was no guarantee that their mail would reach the intended recipient, particularly if the letters contained descriptions of the harsh conditions or cruel imprisonment. As such, many of the letters that survive do not provide us with accurate information about conditions in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Another cruel trick played by the Nazis involved forcing Jews to write letters describing their situation in glowing terms, when this was not at all the case. Or in some cases, letters were typed and the recipients could not be sure that the sender actually wrote them at all or was even still alive.

Back to top

Story:

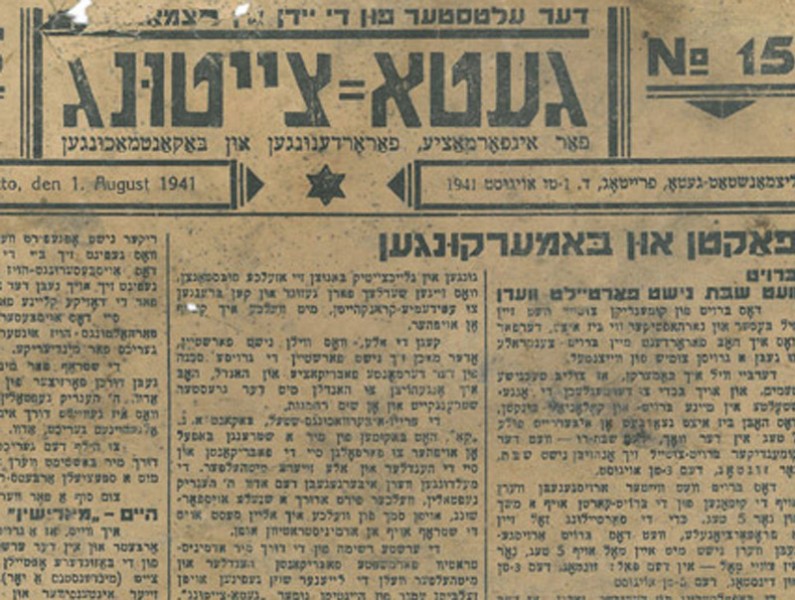

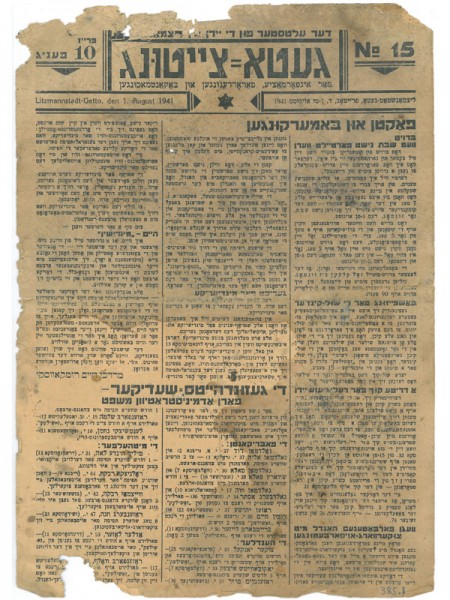

Ghetto Newspaper

A newspaper was published in Yiddish in the Lódz ghetto from March 4, 1941 to September 21, 1941. It was an official paper, produced under supervision of the Judenrat (Jewish Council). The Jews in the ghetto were not allowed to read newspapers or receive any information from outside the ghetto.

Back to top

Story:

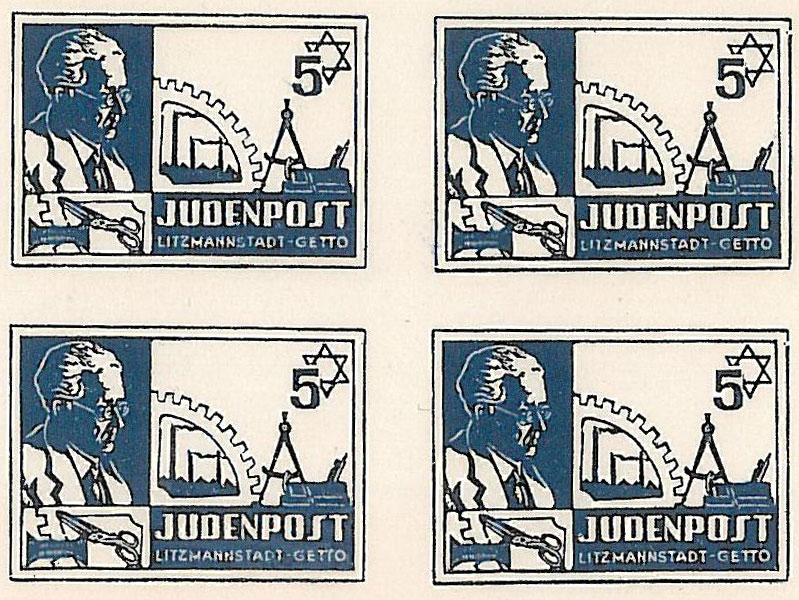

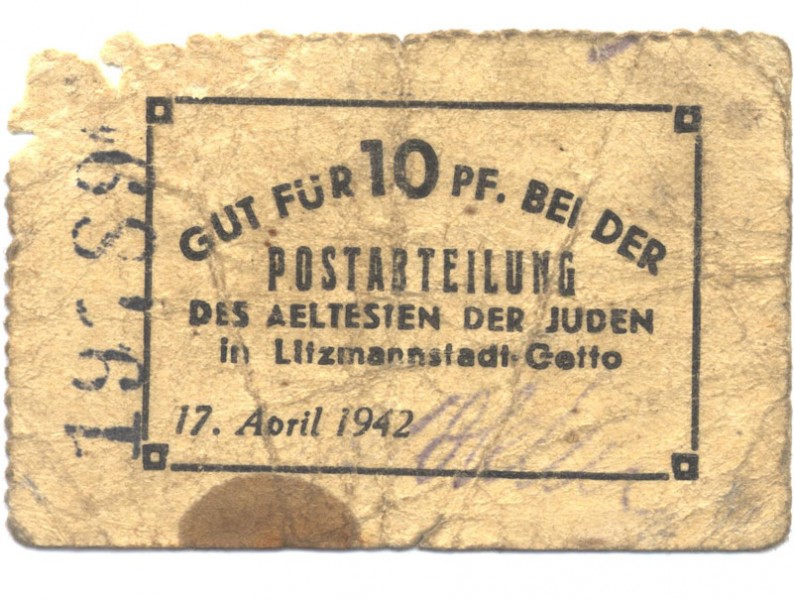

Postal service in the ghetto

In March 1940 the authorities established a ghetto postal service. The post office was in the building at 4/6 Plac Koscielny with a branch office at 1 Dworska Street. Postal workers distributed mail throughout the ghetto. A stamp was produced with the Jewish leader, Chaim Rumkowski’s image on it, but never actually circulated.

At different times in the ghetto history, there were different restrictions on mail. For instance, from June 1940 for two and a half months, no mail could be sent from the ghetto, but could be received. In July 1941, mail was restricted to and from Belgium, Holland and France. All correspondence, incoming and outgoing, was subjected to censorship.

Back to top

Story:

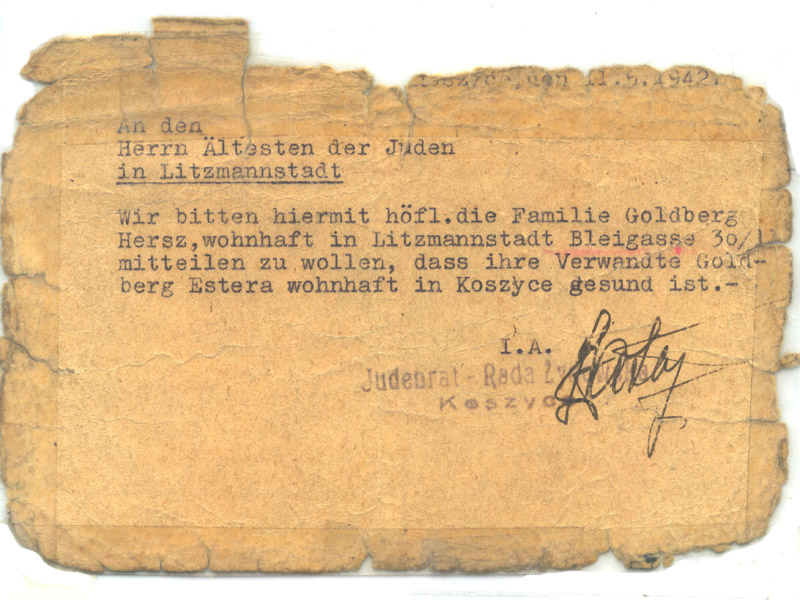

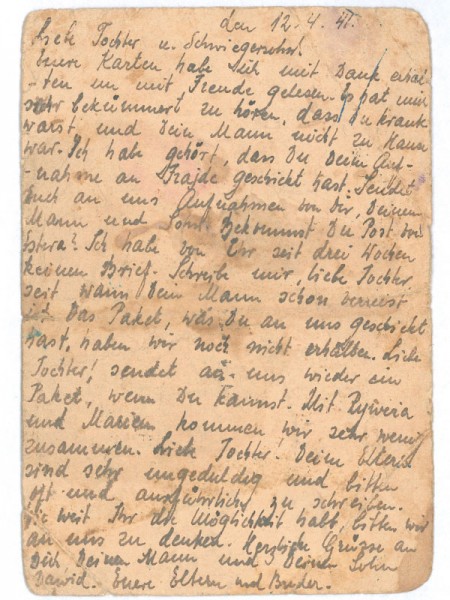

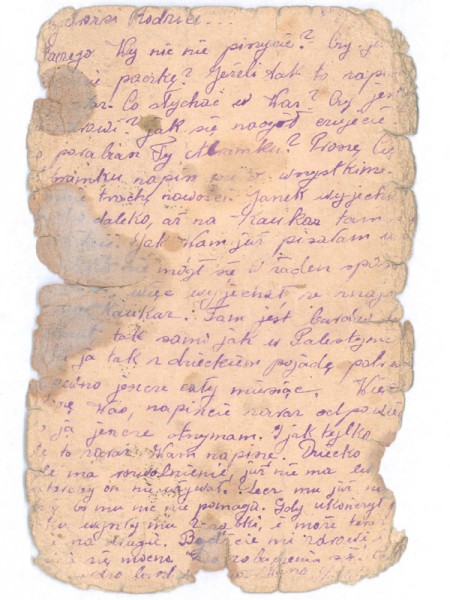

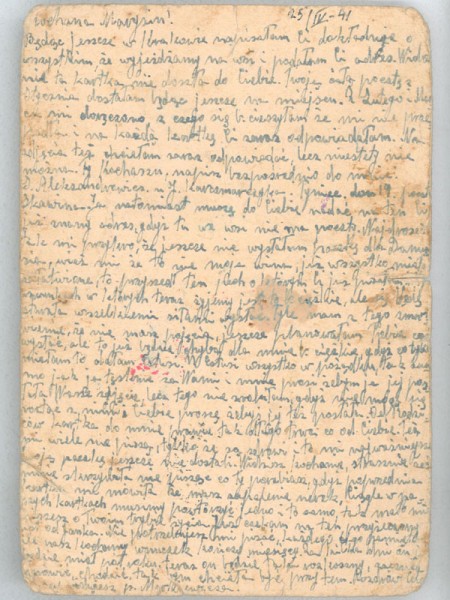

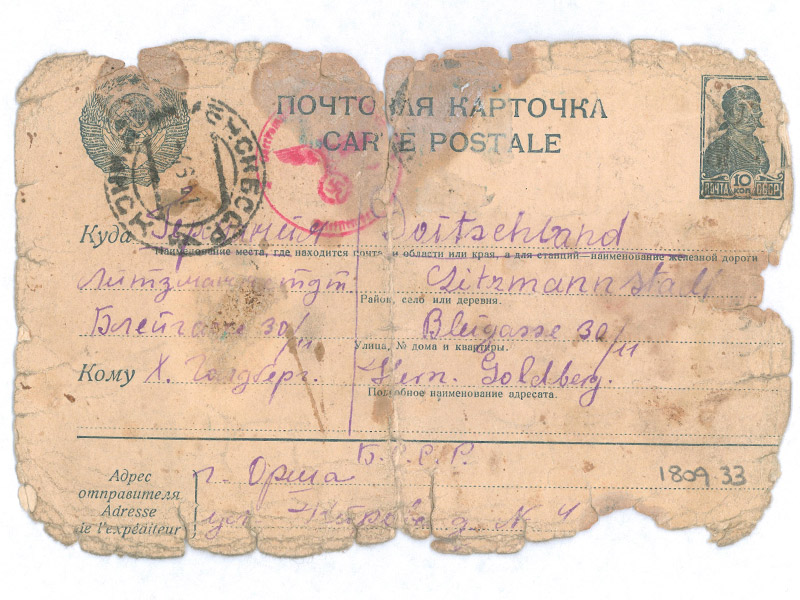

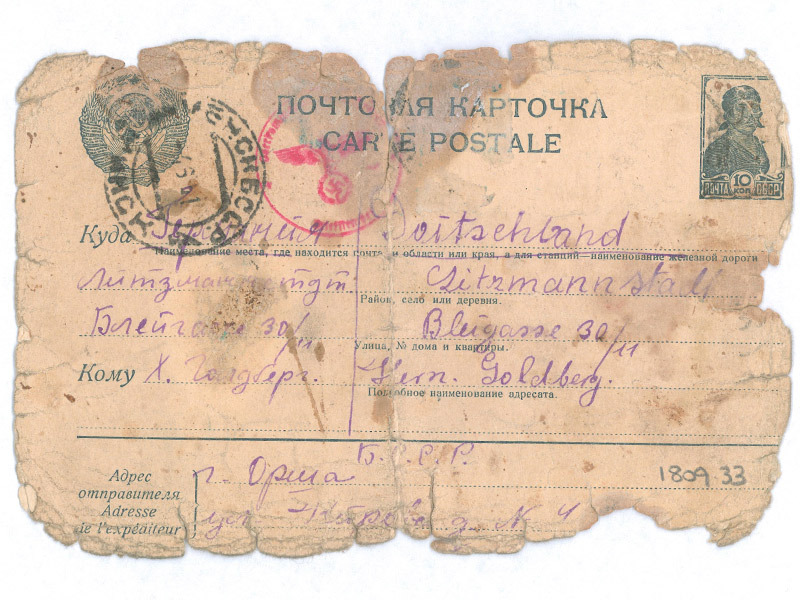

Last letter from Estera

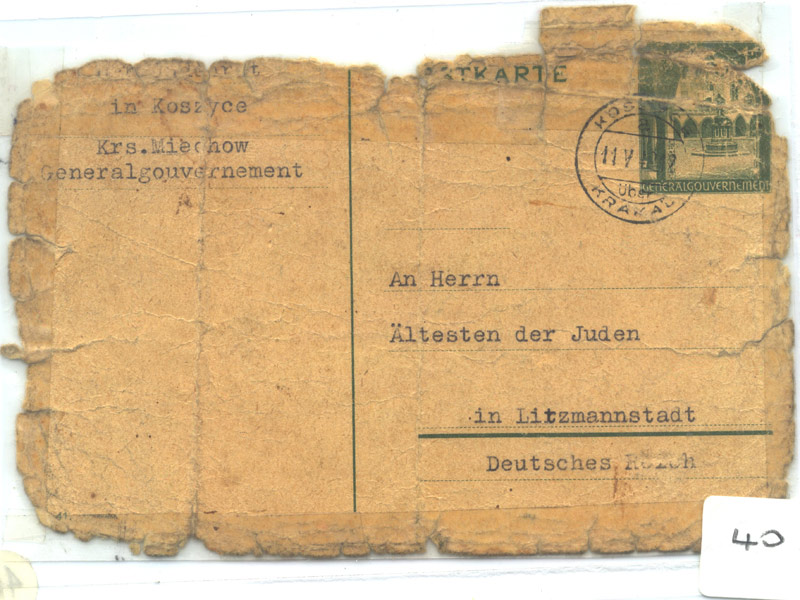

After Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Goldberg family were deported from their hometown of Lodz to Radogoscz concentration camp, before being sent to a makeshift camp near Krakow. Abram’s parents, Hersch and Chaja, had Bund connections in Krakow, which enabled them to travel illegally back to Lodz. Abram went with them but they left his two unmarried sisters, Estera and Frania, behind. The Goldbergs intended to return to collect the girls, but after the closing of the Lodz ghetto on 1 May 1940, they were unable to reach them. The family received irregular letters from Estera, including this postcard on 11 May 1942, informing them that Estera was now residing in Koszyce.

Abram recalls: “In 1942 this came in the ghetto, addressed, not to us personally, but to the Elders of the Jews in Litzmannstadt (Lodz). On the other side, was printed that my sister, Estera Goldberg, was living in Germany. To let us know that she was alive and well? Was she still alive at this time? I don’t know. It is her name. The signature was supposed to be from the Judenrat (Jewish Council) in Koszyce.”

It is difficult to ascertain whether this document was written by Estera herself, and whether she was even alive by 1942 because the Nazis often forced camp inmates to write to their loved ones, allaying their fears about deportation in an attempt to convince others to join them. Sometimes inmates were forced to write multiple letters, which would be posted after the author’s death. Abram never found out the fate of either of his sisters. His third sister, Maryla, survived because she had moved to the Soviet Union with her husband.

Back to top

Story:

Illegal radios in the ghetto

As part of the Nazi strategy to control Jews in the ghettos, they were denied access to all forms of media. However some of the Lodz Jews, working in the resistance, decided to build their own radios and listen to them illegally. The news from abroad gave them hope.

The way they did this was to take parts from the German radio that the Nazis had mass produced when they came to power in 1933, which was their way of spreading their propaganda throughout Germany cheaply and effectively. This radio was known as the Volksempfanger. One Jew in particular, an electrical engineer called Viktor Rundbaken, worked for the German Criminal Police (the Kripo) repairing their radio equipment. While doing this work he began stealing parts and secretly building radios for the underground. Unlike the German radio which was designed to only receive German broadcasts, Viktor designed the illegal radios to pick up the BBC and also SWIT (meaning ‘dawn’), the radio station of the Polish Government-in-Exile, broadcasting from London.

Many of the Jews were caught on 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day. The Jews heard about the D-Day Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France on their radios and the news spread rapidly through the ghetto. This prompted the Germans to wonder how they were aware of information that was not yet publicised in Germany. They invaded the ghetto looking for radios and found several and arrested and murdered a number of Jews.