Story:

Passive resistance

In the tightly controlled Lodz Ghetto, Jews had to keep up their spirits by maintaining cultural activities and finding ways to keep hope alive. While this was immensely challenging, the strong will and determination of core elements within different political and cultural groups, managed to keep it going. Clandestine schooling, secret musical performances, listening to news on illegal radios are just some examples of how the Jews defied the Nazis. These activities, collectively referred to as passive resistance, helped keep the spirits of the populace up, when there was little opportunity to get hold of guns and wage a more active resistance to the Nazi oppression. Some survivors talk about acts of sabotage in the factories, which had to be relatively small to avoid detection and punishment, but nonetheless each of these acts served to lift the spirits of the incarcerated Jewish slave labourers.

Back to top

Story:

The Bund

The Bund was a Jewish community organisation that strove to improve life in the ghetto, by establishing a soup kitchen, and sporting and cultural activities. The Nazis banned the group, so members met in small groups to avoid detection. Although wide scale armed resistance was impossible in Lodz, due to Rumkowski’s authoritarian rule and the ghetto’s isolation from the outside world, the Bund contributed in other ways. They organised resistance activities such as removing parts from products which were being manufactured for the Germans, and attempting to procure and construct weapons.

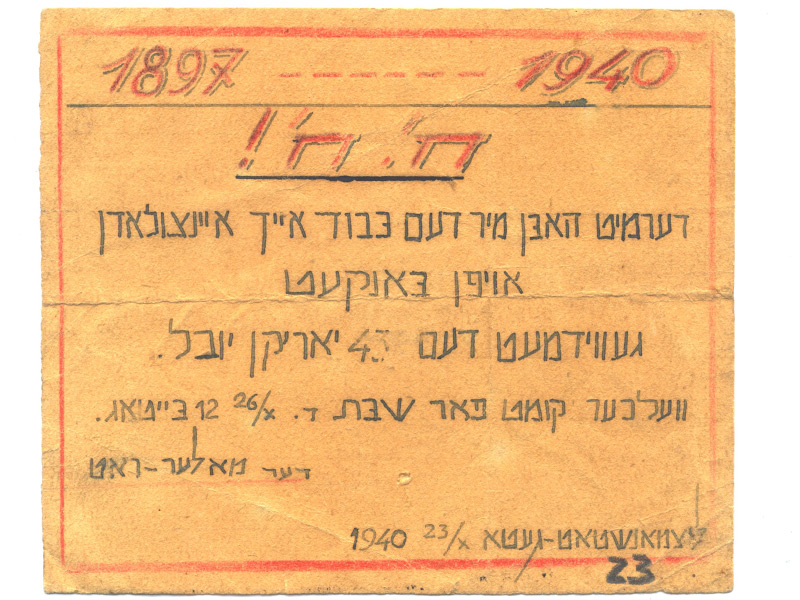

Bund, an abbreviation for ‘the General Jewish Labour Bund of Lithuania, Poland and Russia’, was a secular Jewish socialist party founded in Vilnius, Russia in 1897. They sought to unite all Jewish workers in the Russian Empire into a united socialist party. The Russian Empire then included Lithuania, Latvia, Belorus, Ukraine and most of present-day Poland. The Bund came to oppose Zionism, arguing that emigrating to Palestine was a form of escapism. They promoted the use of Yiddish as a national Jewish language, rather than reviving Hebrew, as Zionists preferred. They had a youth group called ‘Tsukunft’ (Yiddish for future).

During the liquidation of the ghetto between July and August 1944, the Bund were instrumental in warning inhabitants to avoid joining transports to Auschwitz, and to help them hide in the ghetto for as long as possible.

Back to top

Story:

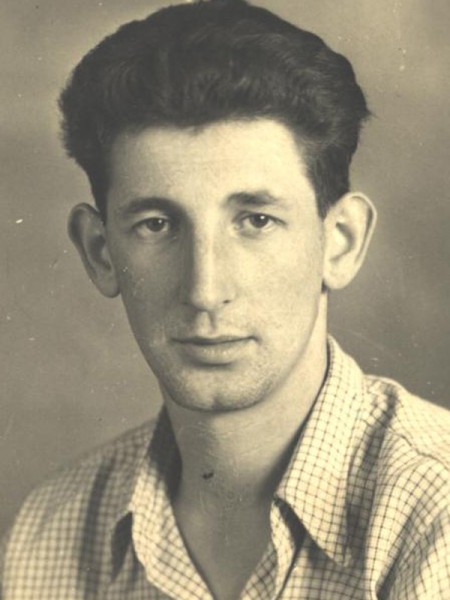

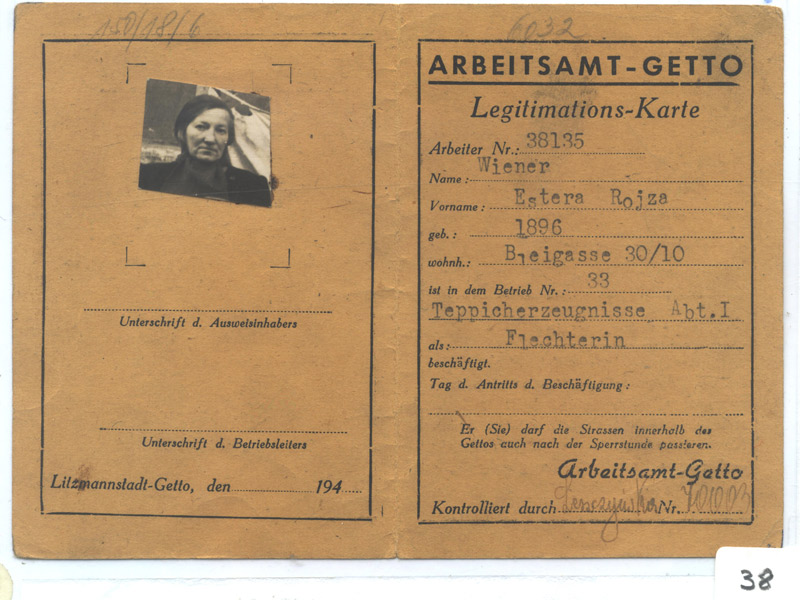

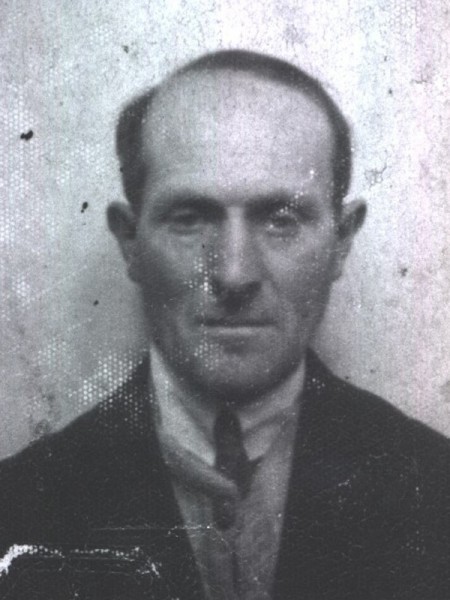

Bono Wiener: political activist

Bono Wiener was 19 years old when war broke out. He was already politically astute, having been brought up with parents active in the Bund movement, a Jewish socialist organisation. In the ghetto he was involved in the resistance movement, and finally, when the ghetto was being liquidated, he was prescient enough to understand the importance of burying documents from the ghetto for the future. While others were thinking about their own survival, Bono had the foresight to see the value in preserving documentary evidence of the Nazi crimes.

Symcha-Binem (Bono) Wiener was born in Lodz in 1920. His father, Mosche, ran a transportation business. His mother, Royze, was involved in the Bund’s women’s organisation. His brother, Pinchas, was a conscript of the Polish Army and spent most of the war in Russia. Bono was a member of the Bund Youth Organisation, the Socialister Kinder Yiddish Farband (SKIF) and was employed as a mechanic in a textile factory when he finished school.

In May 1940, the Wiener family moved in to the ghetto where Bono was employed in a metal factory. He joined the Bund leadership in the ghetto, a group banned by the Nazis. The organisation met in cells to avoid detection and was instrumental in improving the lives of inhabitants in the ghetto. They established a soup kitchen, organised cultural activities, and with the help of Bono, constructed a radio, which gave them access to information about both Nazi and Allied activities. Bono’s father died of starvation on 16 May 1942, while his mother passed away on 30 June 1944, due to complications from kidney surgery. After his mother’s death, Bono’s Aunt Clara was chosen for deportation from the ghetto, so Bono volunteered to accompany her. The couple arrived in Auschwitz on 25 August 1944 and were immediately separated. Bono never saw his aunt again. Bono obtained a position as a toolmaker in Auschwitz and was once again involved in the underground movement.

In mid-January 1945 Bono, aged 24, was sent on a death march to Mauthausen concentration camp. Many prisoners froze to death along the way, due to the harsh Polish winter or were shot by the German guards. Bono survived and was soon employed in a factory in Mauthausen, building planes for the German administration. The United States Army liberated the camp on 5 May 1945.

Bono did not believe it was possible to rebuild a Jewish life in Poland, and immigrated to Australia with his brother in 1950. Bono became active in the Australian Labor Party, was a secretary and president of the Bund, and was one of the Founders of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum in Elsternwick, where he worked as co-president. He died on 9 July 1995.

Back to top

Story:

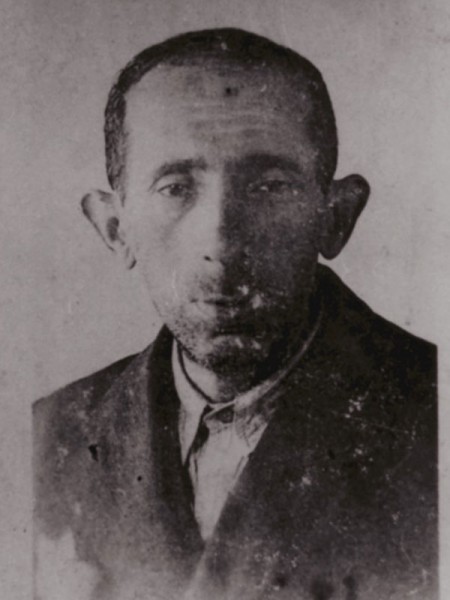

Abram Goldberg: political protege

Abram (Abe) Goldberg was only fourteen years old when war began. He had already been active in the Bund (Jewish socialist) youth organisation since he was ten years old. In the ghetto he befriended Bono Wiener. Bono looked after the younger Abe, and got him involved in the political underground. Before the ghetto was liquidated they collected and buried two boxes of documents and photos, one of which was retrieved by Abe after the war.

Abram was born 5 October 1924 in Lodz. His father, Hersch was a textile worker, and his mother, Chaja, a homemaker. He also had three sisters. After Germany’s invasion of Poland, the Goldberg family were deported from Lodz to Radogoscz concentration camp, before being sent to a makeshift camp near Krakow. Abe and his parents travelled illegally back to Lodz, leaving Abe’s two sisters, Estera and Frania, behind. They intended to return to collect the girls, but after the closing of the Lodz ghetto in May 1940, Abe’s father was unable to reach them. They did not see them again. When the Goldbergs returned to Lodz, they found a room in the same apartment as the Wiener family, and Abe and Bono became good friends. Bono was a supervisor at a metal factory and despite Abe’s lack of experience, gave him a position as deputy foreman.

During September 1942, a mass deportation occurred in the Lodz ghetto in which 15,859 children, elderly and ill inhabitants were transported to Chelmno extermination centre. Abe’s father, aunts and six cousins were caught hiding during selections and included on the transports. Abe and his mother somehow carried on, working and starving in the ghetto. At the beginning of August 1944 the Germans commenced the liquidation of the ghetto and deportation to Auschwitz. Abe and his mother decided to go into hiding in the ceiling of their apartment. During the night, they could leave their hiding place to find food and water. After four weeks Chaja decided to present herself for deportation, so Abe accompanied her. When they arrived in Auschwitz, they were separated immediately, and Chaja was sent directly to the gas chambers.

Abe worked as a metal worker in Auschwitz, then was transferred to Braunschwieg camp in Germany where he cleaned engine parts in a truck construction factory. During March 1945, inmates from Braunschweig were forced on a death march to Watenstadt, then sent to Ravensbruck camp and later transferred to Wobbelin, where he was liberated on 2 May 1945.

After the war, Abe returned to Poland to collect the buried boxes of artefacts. He worked for the Bund organisation, assisting Jews to escape Poland and find new homes. He met and married survivor Cesia Amatensztein in Belgium. They decided to leave Poland, where the majority of their families were murdered, apart from Abe’s sister Maryla, who had moved to the Soviet Union with her husband before the war. Abe and Cesia immigrated to Melbourne. He became involved with the Melbourne Holocaust Museum in 1984 where he served as treasurer and is still active as a museum guide and member of the Board.

Back to top

Story:

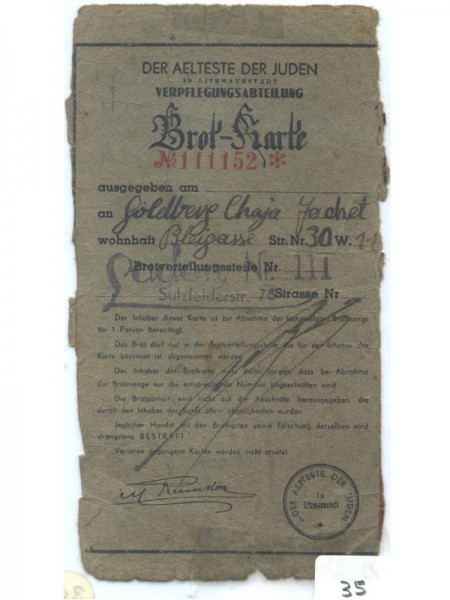

Burying the boxes

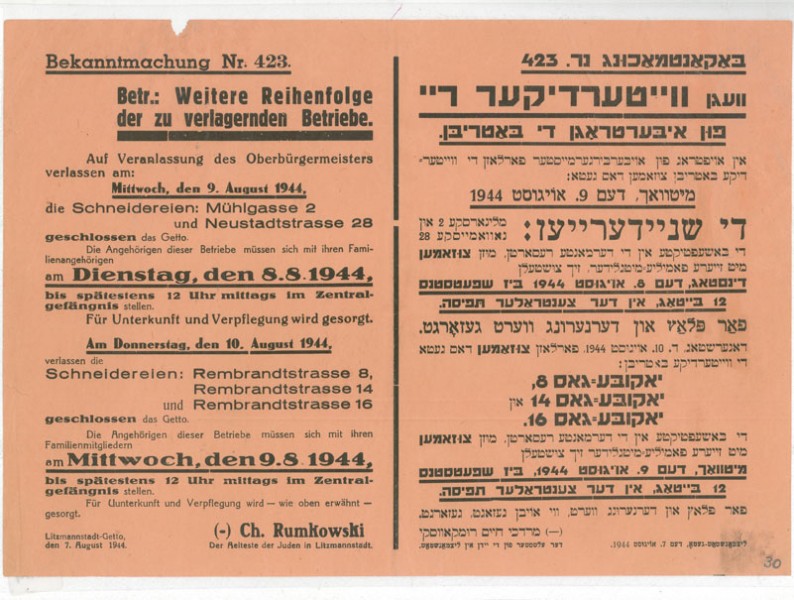

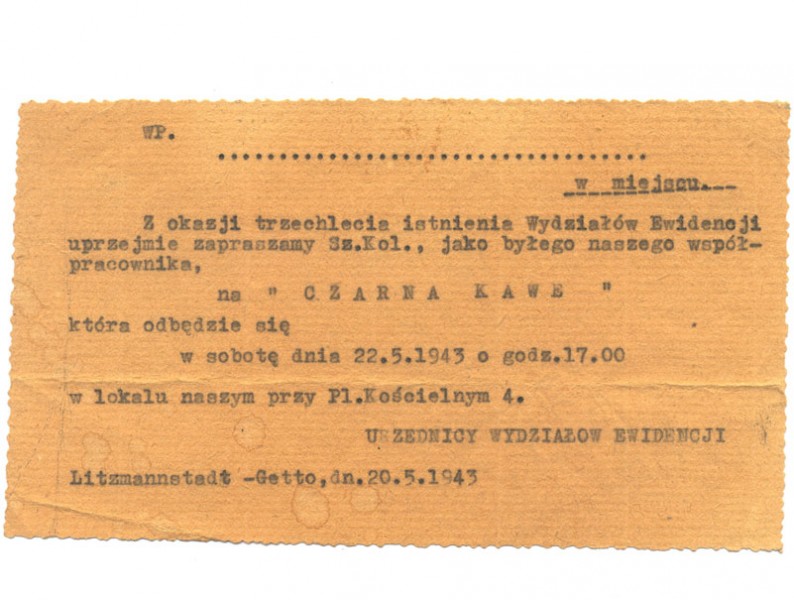

Secretly, in 1942, Bono Wiener and Abram Goldberg began collecting artefacts in the Lodz ghetto. They hid the material in their apartment attic. The items included official ghetto notices and orders, ration cards, work cards, an illegally-constructed radio, as well as a variety of other invaluable documents. Both Abram and Bono were politically active in the Bund (a Jewish socialist organisation) and collected the material as evidence of the conditions in the ghetto. The items testify to Rumkowski’s authoritarian rule of the ghetto, and give an insight into the hardships faced by ghetto inhabitants.

During the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto, between July and August 1944, Abram and Bono hid two metal boxes containing the artefacts. One was buried under a toilet, which they hoped would deter thieves, owing to the stench. The second box was buried in a garden under trees. After liberation, Abram, who heard that Bono had died in Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, returned to Lodz in May 1945. Although he retrieved the box hidden in the toilet, he failed to find the second box containing the radio and some of his diaries.

Back to top

Story:

Secret Radio

As part of the Nazi strategy to control Jews in the ghettos, they were denied access to all forms of media. This was no more successful than in Lodz Ghetto, which was located inside the Greater Reich, and totally cut off from the rest of the world. For some time there was a newspaper produced in the ghetto but its contents were tightly controlled by the administration.

Accordingly, the Jews were cut off from any knowledge of what was happening in the war, except for the occasional news that came via a brave courier from another ghetto. There was a political underground in the Lodz Ghetto, so at some point they asked Viktor Rundbaken, a Jewish electrical engineer who fixed radios for the German Criminal Police (the Kripo), whether he could build a radio for them to listen to overseas broadcasts. He built several radios, and by listening to them in secret, at risk of death, these Jews learnt what was happening beyond the ghetto walls. They disseminated this information through the ghetto via a network of informers, spreading hopeful news to sustain the Jews who were not just starved of food, but desperate for a reason to cling on to life.

Viktor Rundbaken was both ingenius and courageous in building these radios. When repairing a radio for a German official, he would secretly steal a part or two, then request these parts be ordered to fix the radio, claiming they were broken. The radios he built for the Jewish resistance were made exactly from parts found in the Volksempfanger, the German people’s radio. This was the ultimate sabotage, turning the German propaganda device into a weapon of hope for the incarcerated Jews. For not only did he build a working radio, but Viktor made it do just what the German radios were designed specifically not to do: pick up overseas broadcasts.

When the Jews secretly listened to their radio they were trying to tune into either the BBC broadcast or SWIT (meaning ‘dawn’), the radio station of the Polish Government-in-Exile, broadcasting from London.

Although it is impossible to be precise, about six clandestine radios were known to exist in Lodz Ghetto. Most of these were confiscated by the police on 7 June 1944. This was the day after D-Day, when the Allies landed at Normandy and began to defeat Germany. The Jews listening to radios heard about this and became elated at the news. They were aware that the Soviet forces had advanced into Poland and were near. They knew that D-Day marked a turning point. Unfortunately their excitement caused them to make mistakes and the news spread too quickly through the ghetto. German officials station in or around the ghetto began to hear the news, news that was not yet being broadcast through German radio. They became suspicious and embarked on an extensive raid to locate the radios that they presumed were the source of this information. They captured and arrested a number of Jews and their radios. We know of two that survived. One belonged to Weksler and survived the war and was donated to the Ghetto Fighters’ House in Israel. The other was buried by Abe and Bono, but was in the box that was presumably found by looters.

Back to top

Story:

Street performers in the ghetto

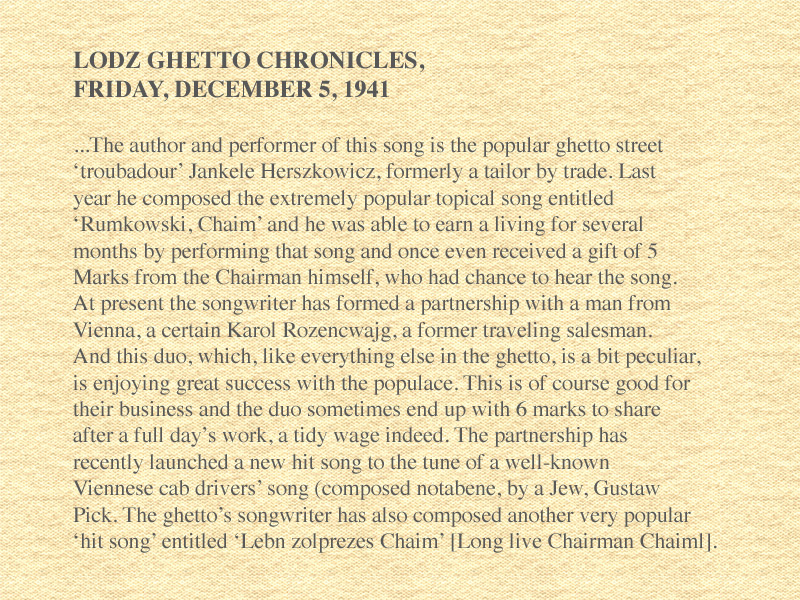

Particularly in the early years, street entertainers performed regularly, expressing the struggle and suffering of daily life in the ghetto. The street performers were able to offer the populace a source of much-needed humour, particularly in the form of parodies of popular songs, in response to the worsening conditions in the ghetto. The performers sang for an audience hungry not only for food but also for freedom of expression. Their spontaneous performances of social and political satire were much appreciated in an environment where information was highly controlled and censored.

Out of the many street performers in the ghetto, Yankele Hershkowitz is particularly well known. Initially he performed alone, but was soon accompanied by a Viennese violinist, Karl Rosenzweig. An unlikely duo, forced together by strange circumstances, they always attracted a crowd. Survivors recorded Hershkowitz’s songs after the war.

The Jewish authorities increasingly censored these performances, and they ceased at the end of 1942. After the mass deportation of September 1942, the singers, including Yankele Hershkowitz, could not remain on the streets, as no one could “pay” them in food or listen to them because the ghetto had been converted into a large and productive factory. Hershkowitz continued to perform in the factory where he found work.

Here are some lyrics from Yankele Hershkowitz’s song, “What Shall We Do, Jews?’:

What shall we do, Jews

When there is such tragedy?

What shall we do, people?

We have to eat, every day!

Because the stomach doesn’t want to know

Anything about our ghetto business,

It only screams and demands

To eat and eat some more.

Back to top

Story:

Education, culture and religion

Despite the harsh conditions in the ghetto, the Jews strove to keep education going for as long as they could, as well as cultural and religious activities. For in the absence of adequate nutrition, it was deemed that mental and spiritual stimulation was vital as ‘food for the soul’.

In the early days of the ghetto a proper school for the children was established, but by 1941 it was shut down and all the children who were able were forced to work. Clandestine schooling continued where possible. Some religious activity continued but it too went underground. The ghetto maintained a cultural life for as long as it could, with theatre and musical performances as well as poetry readings. The maintenance of cultural life in the ghetto was a form of resistance to the oppressive conditions Jews were forced to endure in their ghetto prison.

Back to top

Story:

The Weksler Radio

In researching this project we came across a similar radio to Bono’s, also made by Viktor Rundbaken in the Lodz Ghetto, and used by the Weksler family. After the war this radio was donated to Beit Lohamei Hagetaot (The Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum) in Israel.

They sent us the images of the radio that we are using and Abram Goldberg confirmed that the radio Bono used was similar to it, although theirs was able to be split in two.