Story:

Jewish Lodz Before the War

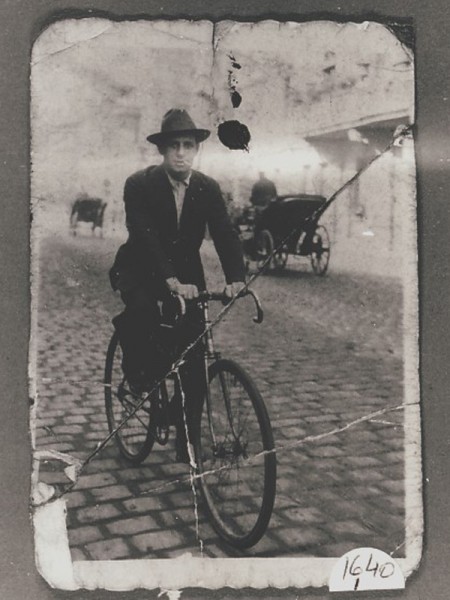

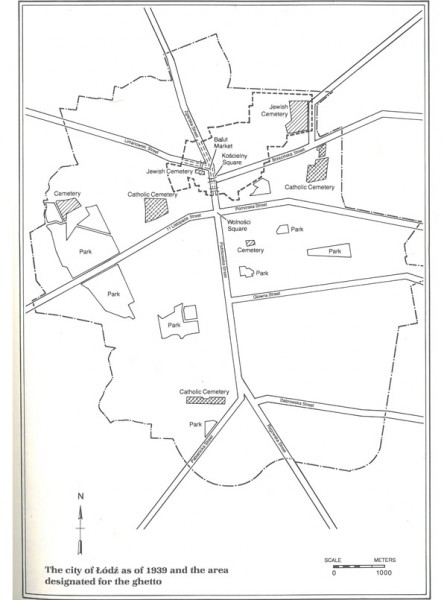

When the war started in 1939, Lodz was the second largest Jewish city in Poland with 223,000 Jews living there, one third of the city’s population.

Lodz was an industrial city and its main industry was textiles. It was often referred to as ‘the Manchester of Poland’. Jews were heavily involved in this industry, at every level, from entrepreunerial factory owners to impoverished factory workers.

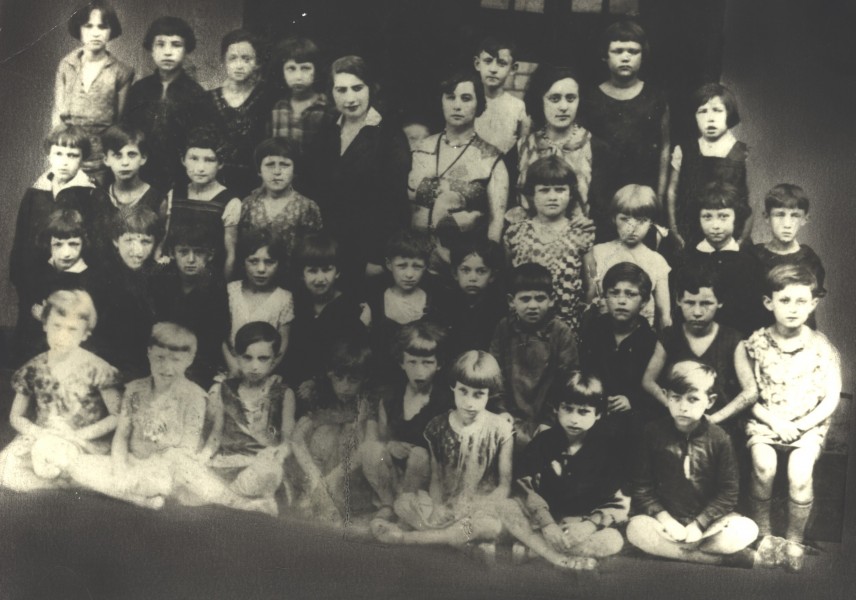

The vibrant Jewish community was very mixed, from deeply religious Hassidic Jews to secular socialist Bundists. Some were Zionists, others were not. There were many schools and community organisations, including welfare organisations.

Back to top

Story:

Nazi Invasion

World War Two began when the German Army invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. When the Nazis attacked, Poles and Jews in Lodz worked frantically to dig ditches to defend their city. Only seven days after the attack on Poland began, on September 8, Lodz was occupied. Within days of Lodz’s occupation, the Jews of the city became targets for beatings, robberies, and seizure of property. Six days after the occupation of Lodz, it was Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year), one of the holiest days. The Nazis ordered businesses to stay open and the synagogues to be closed, knowing the Jewish religion required Jews to worship and not work on this day. One month later the Nazis burned down one of Lodz main synagogues, on Wolborska Street.

On November 7, Lodz was incorporated into the Third Reich and the Germans changed its name to Litzmannstadt (“Litzmann’s city”) – named after a German general who died while attempting to conquer Lodz in World War I. The Germans forced many Jews to leave Lodz and deported them to cities in the General Government. Between September 30 and May 1, 1940, over 60,000 Jews left Lodz.

Back to top

Story:

Life in the Lodz Ghetto

In 1940 Jews were concentrated and imprisoned in a ghetto and forced to work as slave labourers. Lodz Ghetto lasted until August 1944, longer than any other ghetto in occupied Poland. During that period around 60,000 Jews died from disease, starvation and overwork. The rest were sent to concentration and extermination camps where most were murdered. It is estimated that only 10,000 Jews from Lodz Ghetto survived the Holocaust.

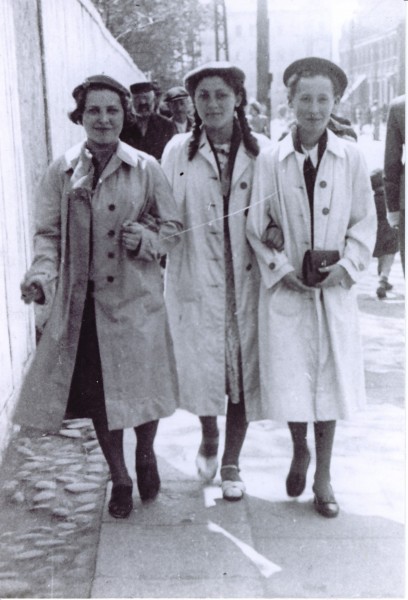

Immediately after the occupation, the Nazis implemented repressive measures against the Jews. Jews were ordered to wear the Star of David on their chest and back, their bank accounts were frozen and their possessions could be seized. Initially the Nazis wanted the Jews to leave Lodz and make it judenfrei (free of Jews). Approximately 60,000 Jews escaped Lodz before the ghetto was established.

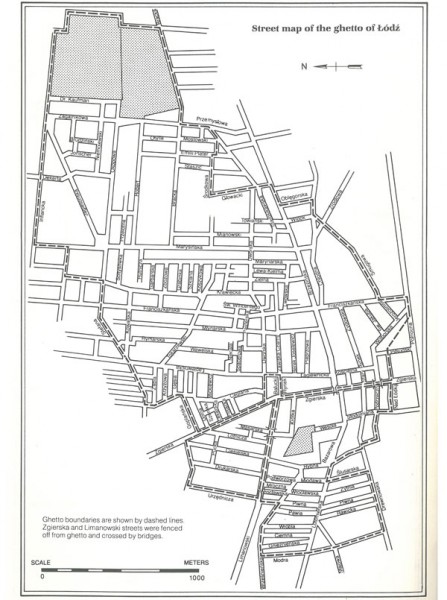

Lodz Ghetto operated from 1 May 1940, when 164,000 Jews were concentrated into a 4.13 km2 dilapidated section of the city. During March and April 1940, the ghetto was hermetically sealed by a wooden and barbed wire fence. Jews were completely cut off and dependent upon the German administration to provide them with food and resources.

The ghetto was overcrowded, and Jews experienced starvation, disease and exhaustion, which led to many premature deaths. Conditions were appaling, most apartments had no inside toilets, no running water and no heating.

During January and May 1942, 55,000 Jews and 5,000 Sinti-Roma (gypsies) were sent to Chelmno and murdered. The second major deportation occurred in September 1942, often referred to as the Sperre, in which 15,859 children, elderly and ill inhabitants were also sent to Chelmno after the German administration decided to transform Lodz into a total labour ghetto. In order to do so, they required these “unproductive elements” to be removed.

After the Sperre, the ghetto entered a period of relative calm, with the remaining Jews working as slaves, starved and exhausted. It was not until the advancement of the Russian Army that the German administration ordered the complete liquidation of the ghetto in June 1944. Between June 23 and July 14, 7,000 Jews were deported from Lodz. On August 2, Rumkowski published a notice in the ghetto stating that the entire ghetto needed to be relocated, although the destination was not mentioned. Between August 2-29 regular deportations took place and approximately 67,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz.

Around 500-600 Jews were left in the ghetto to “clean up” by removing all valuables from the ghetto. Another 300 successfully hid from the deportations. On 19 January 1945, the Russian Army liberated 877 Jews from the ghetto.

Back to top

Story:

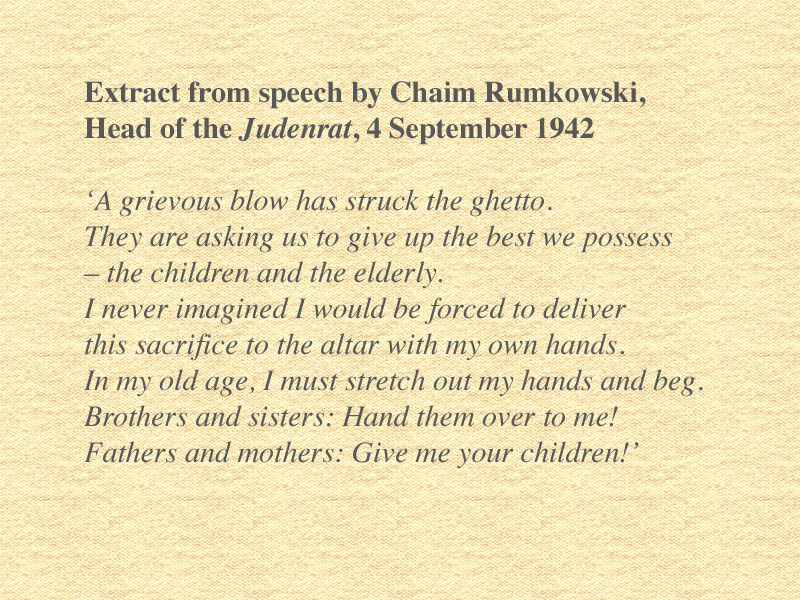

Judenrat (Jewish Councils)

Judenrat (Jewish Councils) were established by the German administration to oversee all internal Jewish affairs in the ghettos, including housing, food, welfare, law and order and employment. In the Lodz ghetto, Chaim Rumkowski was appointed as the head of the ghetto.

As time progressed, the Judenrat were increasingly required to oversee the deportation of Jews for work outside the ghetto. The majority of deportees were sent to concentration and extermination camps. The Judenrat were caught between the need to satisfy German demands, while trying to represent interests of the Jewish community. As Rumkowski complied with German directives, the ghetto populace increasingly saw him as a Nazi collaborator. Although Rumkowski was awarded significant autonomy in the ghetto, the concept of Jewish self-government was, in fact, a façade constructed by the Germans in order to obtain the leader’s cooperation. If he failed to please the German administration he could be instantly dismissed.

Back to top

Story:

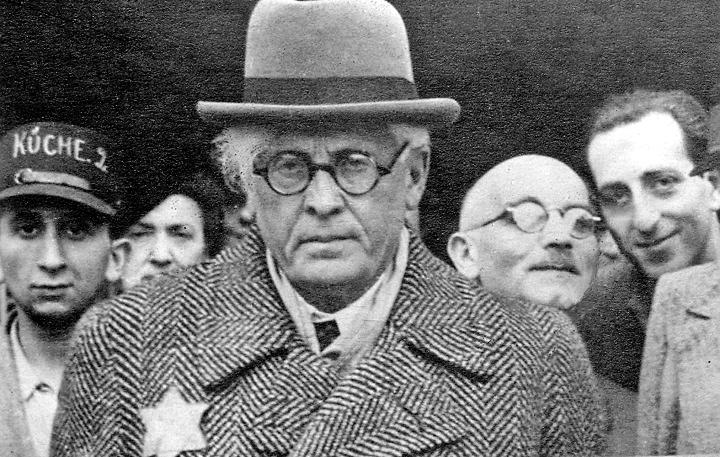

Chaim Rumkowski, Elder of the Jews

Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski was appointed Elder of the Jews in Litzmannstadt (Lodz) on 13 October 1939. As leader of the ghetto Rumkowski adopted what became referred to as the “rescue through labour” strategy, which was used to protect the ghetto from liquidation by providing a huge profit to the German administration. It was successful, insofar as the ghetto remained viable until August 1944. The price for this strategy was that it involved deporting all Jews from the ghetto considered unproductive: children, the elderly and the infirm. For this reason, Rumkowski was much despised. In the end the remaining Jews were deported to Auschwitz, and most, including Rumkowski, did not survive.

Rumkowski was born in Russia in 1877 and it is believed he arrived in Lodz during adulthood. His pre-war employment was in trade and industry. He was Founder and Director of the Helenowek orphanage and involved in the General Zionist Party.

In the Lodz ghetto, Rumkowski was an autocratic leader, solely responsible for the maintenance of the ghetto, with the other Judenrat (Jewish council) members merely figureheads. He had significantly more autonomy from the Germans than most ghetto Elders. What distinguished Rumkowski from other leaders was his success in prolonging the life of the ghetto by mobilizing the ghetto workforce, and his unwavering cooperation with German orders. Rumkowski requested that the Germans provide the ghetto with raw materials with which the ghetto workforce could produce finished goods. He hoped this strategy would make the ghetto economically indispensable to the Reich and the German war effort. By 1943, there were 117 factories, workshops and warehouses in the ghetto. During 1942-3, ninety-five percent of adults in the ghetto were working. Rumkowski’s cooperation strategy prolonged the survival of the ghetto for almost two years.

Rumkowski’s position as Elder did not protect him from the fate of the majority of the Lodz Jews. Like most ghetto Elders, Rumkowski did not survive the war. On 29 August 1944, at the conclusion of the ghetto liquidation, he too was deported to Auschwitz.

Back to top

Story:

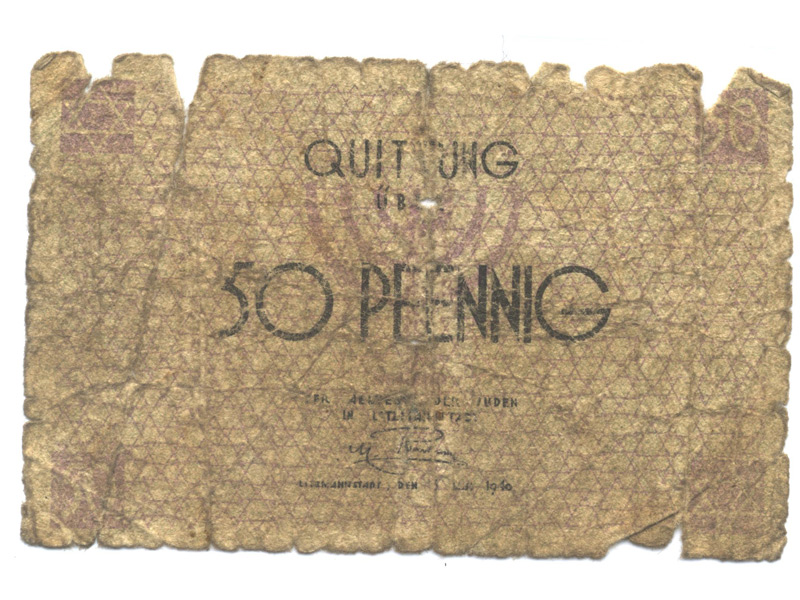

Lodz Ghetto Currency

Lodz ghetto currency or ‘ghetto marks’ became official legal tender in the ghetto on 8 July 1940. They were colloquially referred to as ‘Rumkies’ after Rumkowski, Elder of the Jews. When the ghetto was first established, Jews were forced to sell furniture and other valuables for minuscule amounts of the ghetto currency, for which the Nazi administration made a healthy profit. They also had to exchange any foreign notes they owned, because possession of any currency was forbidden in the ghetto. The administration also determined that Jews were only allowed to hold ‘receipts’ for money; therefore all ghetto notes were inscribed with ‘receipt for’, and the amount. Introduction of this currency was a powerful mechanism for controlling the ghetto populace. It acted as a strong obstacle to smuggling in the ghetto because it was worthless outside of Lodz.

The ghetto notes were printed in the Manitius Printing House, outside the ghetto, under the supervision of the Gestapo, in denominations of 50 pfennig and 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 mark bills (they also minted coins). The bills displayed here are: 50 pfennig, 1 mark, 2 marks and 50 marks. These notes bore Rumkowski’s signature, Hanukkah candles and the Star of David.

The German administration paid so little for goods produced inside the ghetto that worker’s wages barely covered the cost of food. If inhabitants wished to purchase additional food or goods on the black market they could barely afford to due to swollen prices. For example, in 1942 the cost of 2 kilograms of bread rose from between 300-400 marks to 2,000, which was equivalent to two years wages.

One inhabitant was caught forging notes and was imprisoned by the ghetto police on 26 July 1941. He was imprisoned in the ghetto jail and deported to Chelmno extermination centre in January 1942.

Back to top

Story:

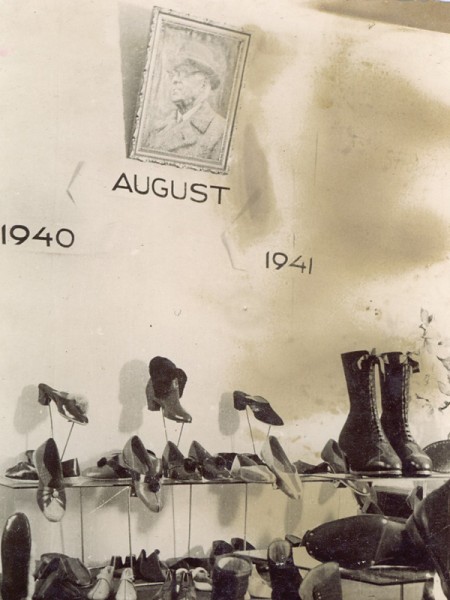

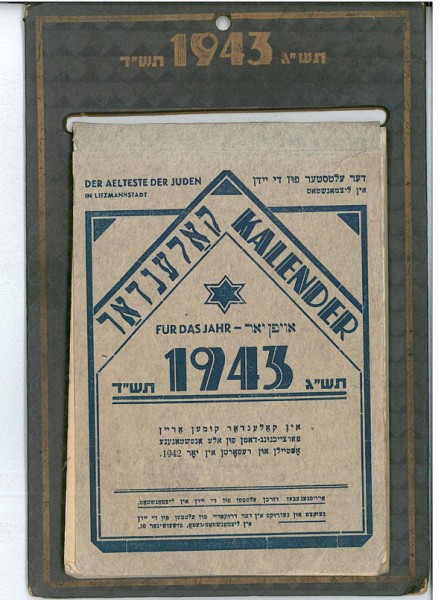

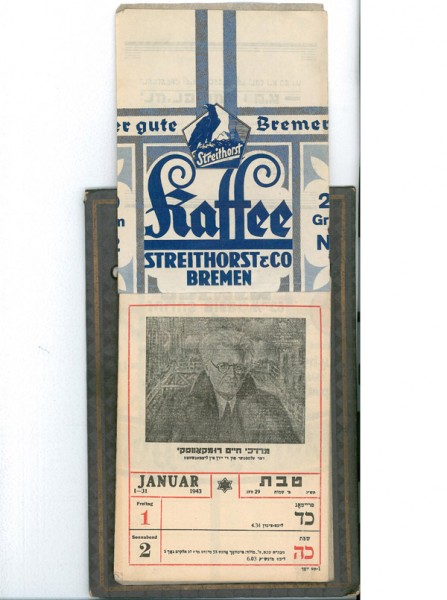

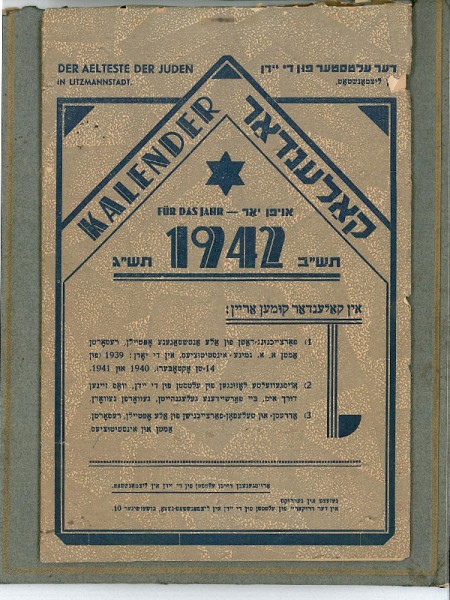

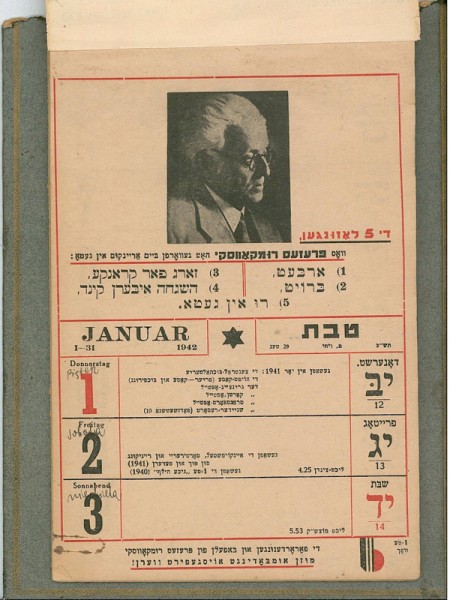

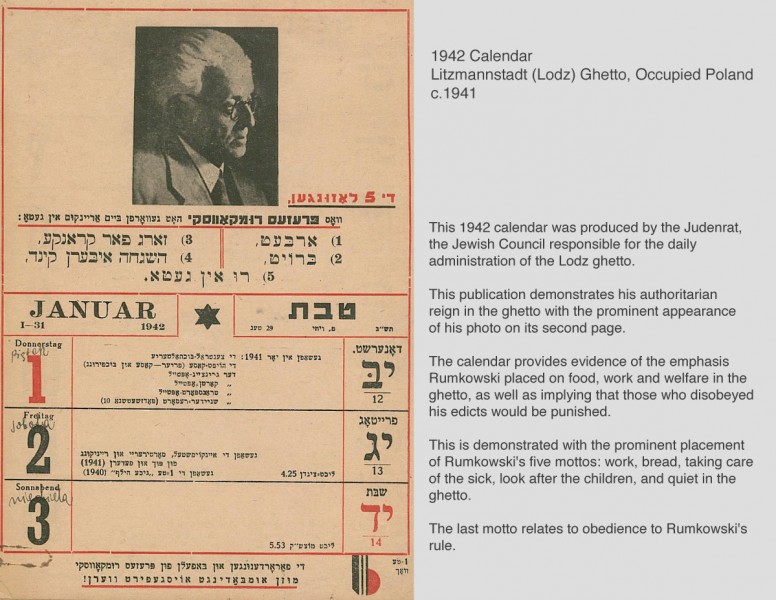

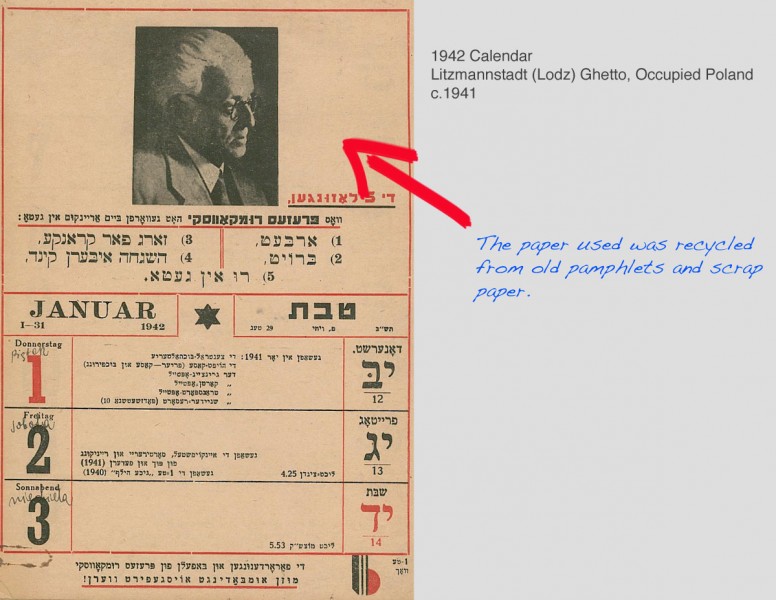

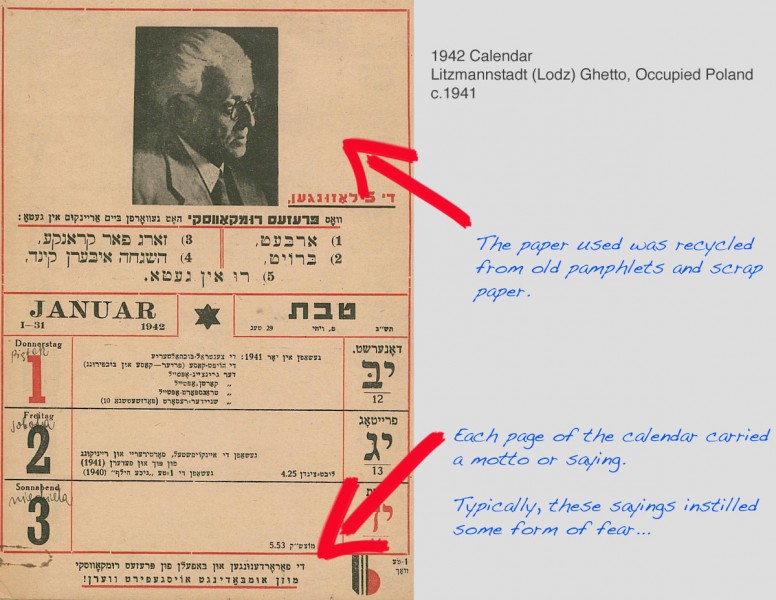

Lodz Ghetto calendar

These calendars were produced by the Judenrat, the Jewish Council responsible for the daily administration of the Lodz ghetto. Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski was the Elder of the Jews in the ghetto, and the 1942 publication demonstrates his authoritarian reign in the ghetto with the prominent appearance of his photo on its second page. The calendar provides evidence of the emphasis Rumkowski placed on food, work and welfare in the ghetto, as well as implying that those who disobeyed his edicts would be punished. This is demonstrated with the prominent placement of Rumkowski’s five mottos: work, bread, taking care of the sick, look after the children, and quiet in the ghetto. The last motto relates to obedience to Rumkowski’s rule.

The calendars include quotes from Rumkowski throughout, such as “for the lazy there is no place in the ghetto” and highlights significant dates related to his achievements as leader of the ghetto, such as the anniversary of when particular departments were established. This document also highlights the Judenrat’s attempt to replicate normal life in the ghetto.

1942 was an important year for the Lodz ghetto. In the first seven months of the year 13,000 inhabitants died of starvation, disease and overwork, in comparison with 11,500 in all of 1941. Between January and May the first mass deportation of 55,000 Jews were sent to the Chelmno extermination centre, located sixty kilometres from Lodz. In September, 15,859 children, elderly and ill inhabitants were also deported. This event was referred to as the Sperre, one of the most horrific events of the ghettos history. These events represented a turning point in Rumkowski’s reign – where Rumkowski’s fiction of autonomy from the German administration had come to an end, because he was no longer able to protect the population from deportation.

Back to top

Story:

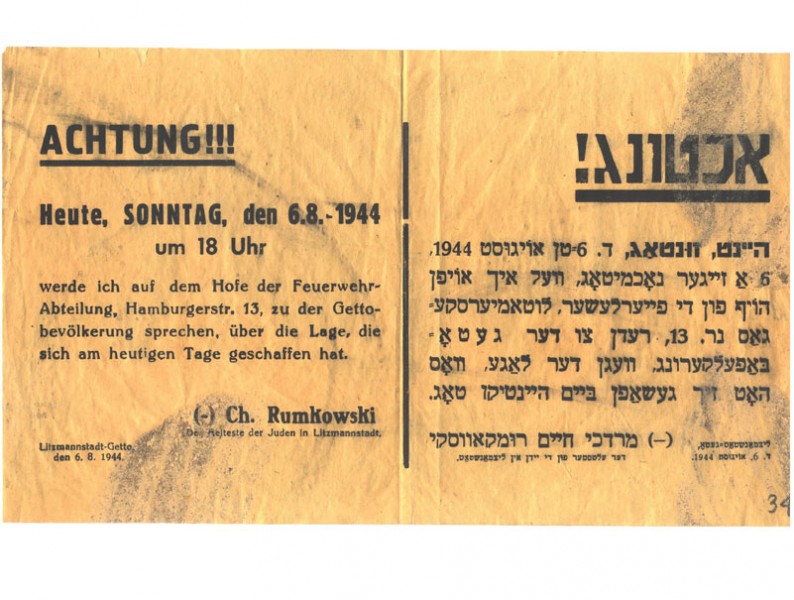

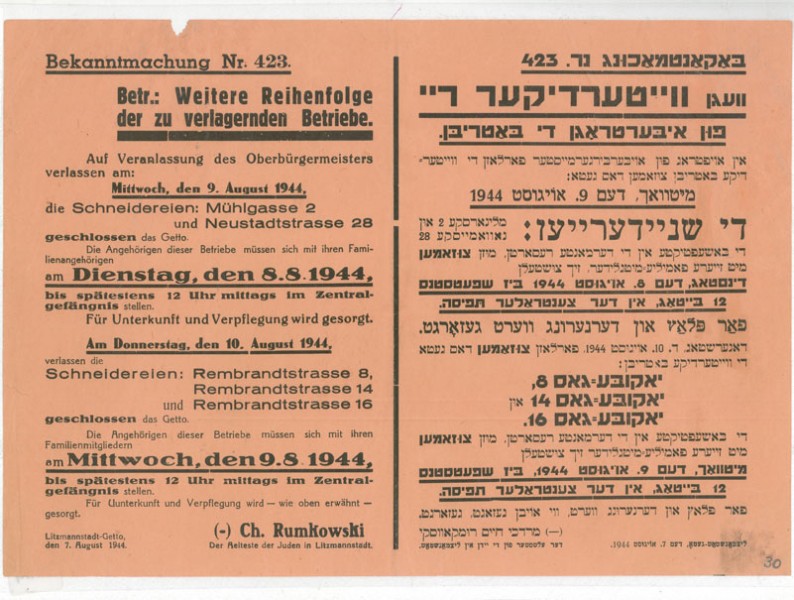

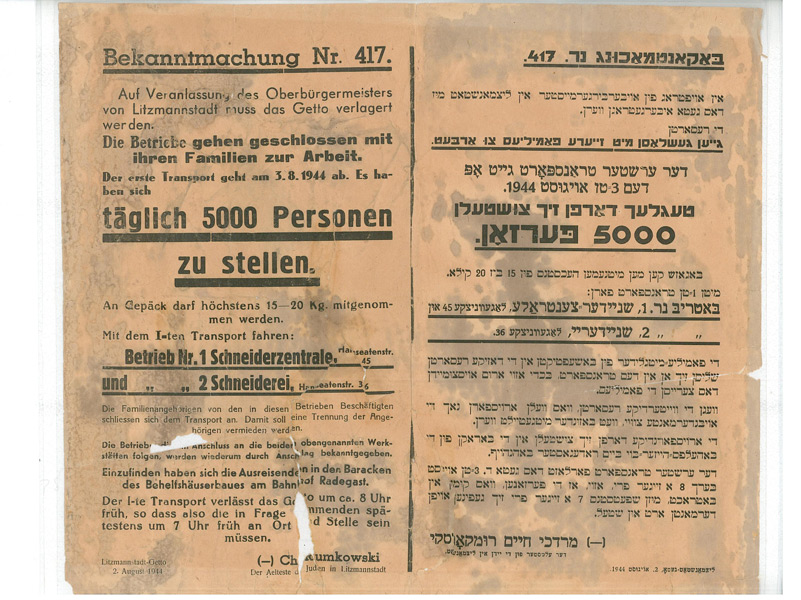

Liquidation of the Ghetto

In 1944 the Nazis increased pressure on the German officials administering the Lodz Ghetto to liquidate it as it was by then the last ghetto in Europe. Hans Biebow, the German administrator of the ghetto, was reluctant to close the ghetto as it was a great source of personal income. Eventually he was forced to submit and in August 1944 the liquidation began.

In order to empty the ghetto quickly and smoothly, the Nazis attempted to deceive the Jews into believing they were being relocated to work camps where they would continue to live with their family members. They were ordered to report to Radegast railway station with their families and with luggage. The reality was that they were being transported to Auschwitz where most would be sent straight to their deaths. Those deemed fit for work were shaved and deloused, their luggage stolen, and then sent to crowded huts, not as families, but men to one bunk, women to another.

By the end of August only 877 Jews were left in Lodz Ghetto, ostensibly to clean it up. The Elder of the Jews of the Lodz Ghetto, Chaim Rumkowski, was on one of the last transports. He was murdered upon arrival at Auschwitz.

Back to top

Story:

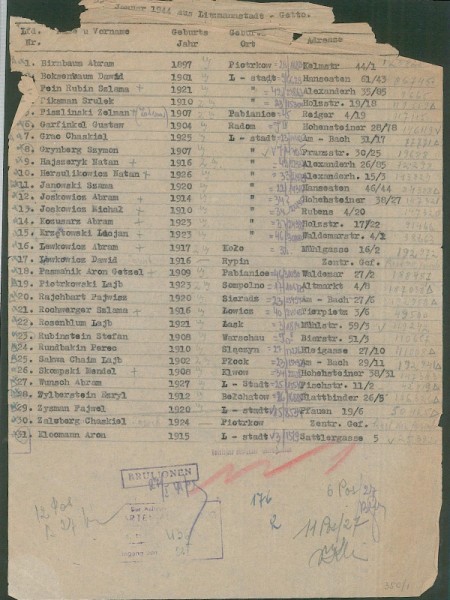

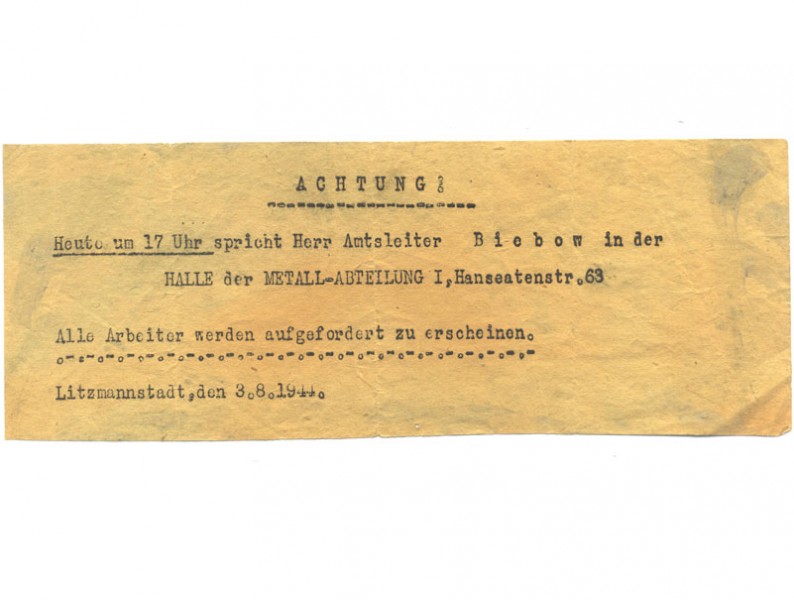

Deportation notice

This notice, calling for the Jews to report for “relocation” to a new camp outside the ghetto, demonstrates the deceptive tactics used by the Nazis to give Jews false hope. By the time of this notice, August 1944, the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto was underway, having commenced in June, with regular deportations to Auschwitz. These deportations were disguised as “relocation” however the new location was never named. The Jews were also deceived into believing that by travelling with their families they would remain together. Yet the majority of family members were separated upon arrival at Auschwitz, and more than 80 per cent were murdered immediately in gas chambers. To add to the charade, this notice states that inhabitants can bring up to 20 kilograms of luggage with them, however they never saw this luggage again.

During August regular notices appeared in the ghetto, ordering 5,000 inhabitants per day, district-by-district, to present for “relocation”. However Jews were reluctant to report. The Bund (Jewish socialist organisation) warned Jews to hide in the ghetto for as long as possible. This particular notice orders workers and their families from two Tailoring Workshops in Hanseatenstreet to report at the Radegast station at 7 am on August 3, 1944.

Although Rumkowski signed this notice, his true authority became clear in the last few months of the ghetto’s existence. His attempts to prevent liquidation ultimately failed. The decision to liquidate the ghetto was made by the German administration, in an attempt to destroy the evidence. When the Soviet army arrived on 19 January 1945, they liberated 877 people. During June and August 1944, over 70,000 Lodz inhabitants were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, with the last transport departing on August 29, 1944 including Rumkowski and his family.

Back to top

Story:

Surviving Lodz

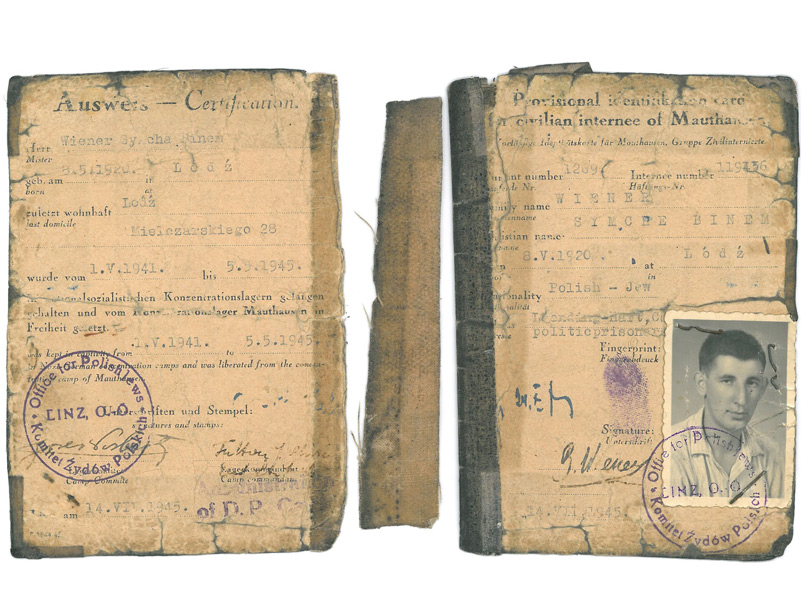

There were 223,000 Jews in Lodz at the start of war, but only around 10,000 of them survived. Starvation, disease and overwork killed many in the ghetto. Those that avoided this fate were sent to camps where they were either murdered upon arrival or died subsequently from overwork and malnutrition.

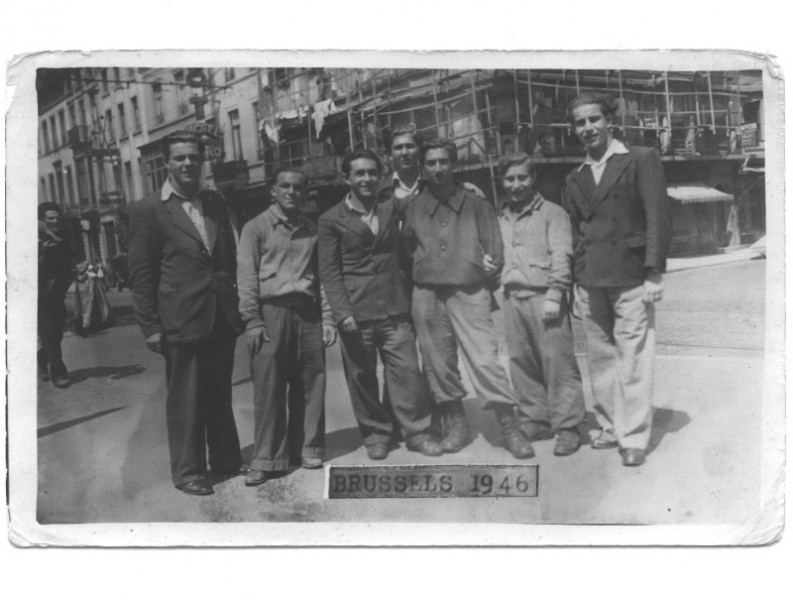

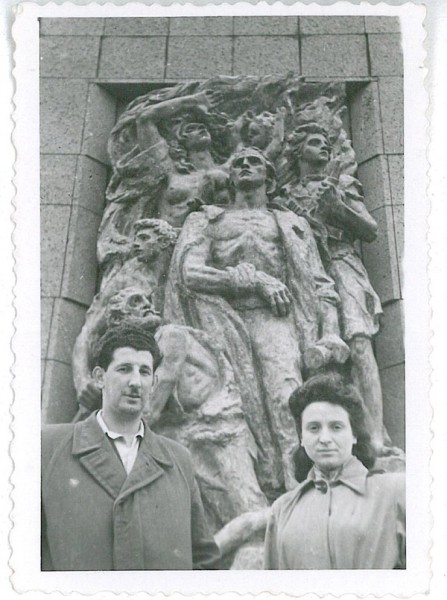

Only 500-600 Jews were left in the ghetto following the final liquidation in August 1944, to “clean up” the ghetto. Another 300 successfully hid from the deportations. On 19 January 1945, the Russian Army liberated 877 Jews from the ghetto. Slowly the surviving Lodz Jews returned and tried to find family, to see if any survived. Some tried to reclaim property and possessions, but this was extremely challenging. There was ongoing antisemitism in Poland, and many of the surviving Jews reported that they did not feel welcome. Many left, going to displaced persons camps to try to build new lives in new countries.